Share this page

By Kevin Philipupillai

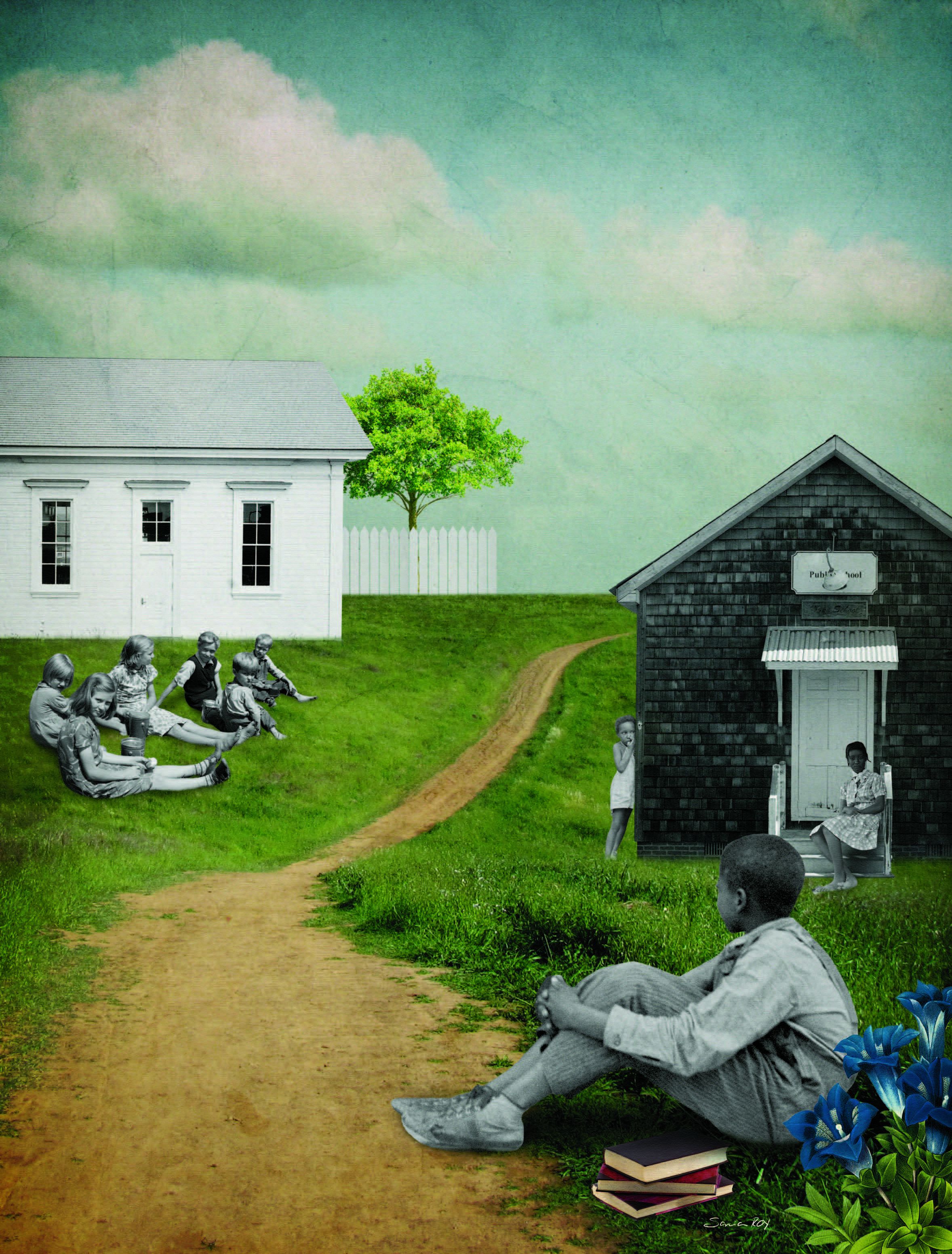

Illustrations: Sonia Roy/Colagene

The Essex County school where Lois Larkin began her teaching career in 1954 was like many other one-room schoolhouses in rural Ontario. The brick building was flanked by an outhouse and a well, and there were 52 children from Grades 1 to 8. But unlike at most Ontario schools, the students and teachers at School Section (S.S.) #11 (Colchester South Township) were all black. “Down the road, within walking distance,” Larkin says, “was the other school. The all-white school.”

S.S. #11 was a segregated school.

During Black History Month, Ontario teachers and students often commemorate milestones in the struggle to end racial segregation in the United States. But segregation was not just an American phenomenon: For more than a century, provincial governments in Ontario and Nova Scotia operated separate schools for black children. In Ontario, the Common Schools Act of 1850 gave local school boards the power to create racially segregated schools, which were most common in southwestern Ontario, home to Canada’s largest historic black population. It would take more than 100 years and a societal shift before Ontario would close its last segregated school, and even longer for those who experienced that racism first-hand to shake off the shackles of feeling second class.

The large influx of black settlers into southwestern Ontario in the 19th century led to racial tensions, which continued well into the 20th century. Harrow, the town closest to S.S. #11, had segregated restaurants and a whites-only movie theatre. “We had sundown laws in this area,” says Elise Harding-Davis, a seventh-generation African-Canadian and former curator of the North American Black Historical Museum in Amherstburg. “Kingsville and Leamington had sundown laws, which meant black people had to be off the streets of the city by sundown. You would not find the laws in the books; they were not written. They were simply public knowledge.”

Local historians are still digging into S.S. #11’s past, but records say the school opened in 1825 as the Matthews School. It was part of a settlement formed by black migrants from the United States — escaped slaves, freedmen and United Empire Loyalists — who had crossed the border into Canada’s southernmost county.

Harding-Davis says most schools for black children had been absorbed into the mainstream school system by 1911. But Essex County and neighbouring Kent County were the lingering holdouts, with S.S. #11 being one of Ontario’s last segregated schools. Larkin remembers the building had one entrance for girls and one for boys. Like at many other one-room rural schools, there was no indoor plumbing and the heat came from a coal-fired furnace that belched smoke.

Glovanna Johnson was one of only two black students in the local high school. She had no friends and no one would speak to her. This stress, plus the one-hour walk to school, built till she had a nervous breakdown and quit school.

The white schools in Essex County were managed by the white members of the county school board, but S.S. #11 had its own board of trustees from the local black community. Provincial funding was based on enrolment, so as a single school drawing from a minority community, S.S. #11’s trustees had to make do with less. Still, Larkin says they made sure the budget was adequate. “And,” she adds, “if we asked for anything, they worked very hard to see that our requests were answered.” Over the years, trustees and other community members did what they could to keep good teachers around, including providing room and board for teachers from out of town.

Beulah Couzzens, who had been teaching at S.S. #11 for more than 20 years, quickly became a mentor and friend to her young apprentice. “She was a very well-travelled lady,” says Larkin, “and I remember her saying that wherever she went, she brought that information back to her children.”

Soon she was encouraging Larkin to expand her own limits. They both knew they weren’t welcome in Harrow’s whites-only restaurants, but Larkin remembers the day Couzzens came into work without a lunch and declared “Today, we will go into Harrow and we will have lunch.” “And we sat at a lunch counter,” Larkin recalls. They were the only two people at the lunch counter, but they sat there for a long time waiting to be acknowledged. “I was just a girl. I was 19,” Larkin says. “But Mrs. Couzzens was determined she was going to be served. She just said, ‘I am going to eat here today. I am hungry and I am going to be served.’ I was scared. I was embarrassed. I had never been at a sit-in, and it was uncomfortable. However, I was determined I was going to stay there with her.” Their determination paid off and they were eventually served.

That same sense of pride, says Harding-Davis, helped sustain S.S. #11 and the few other remaining schools of its kind. There was often disagreement within black communities themselves about the merits of separate schools. Many parents had been fighting for integration since the 1800s, but there were others, including many trustees, who preferred separate schools. There was pride to be found in the success of black schools and black students, explains Harding-Davis, and in the community’s ability to provide jobs for black teachers. Especially encouraging to the black community was a school run by black teachers in Buxton, in Kent County, which had such a good reputation that white parents wanted to, and did, send their children there.

And there were other reasons that, even in the 1950s and ’60s, some black parents in Harrow were hesitant about integrating schools. Glovanna Johnson, who was a student at S.S. #11 in the 1920s, says the school had not always been fully segregated — she had a few white classmates when she was a child. She remembers the younger children, black and white, played together and got along. “My best friend was a white girl,” the 97-year-old says. “I thought the world of Olive Borland.” But integration had its problems too. “I was little and I was frightened easily and the big boys would fight. They would scare me out of my wits. There were four or five big boys — white boys — and they would fight the younger black boys. It wasn’t very pleasant.”

Despite the sometimes uncomfortable school atmosphere, Johnson was a good student. In 1928, when she was 11, she took the high school entrance exam and passed — an achievement that got her name in the newspaper. But things started to go wrong when she started at Harrow District HS later that year. She was one of only two black students in the school, she had no friends and no one would speak to her. This stress, plus the everyday drain of a one-hour walk to school, built until she had a nervous breakdown and quit school.

Harding-Davis has heard similar stories. “These are not stupid people,” she says. “These are very bright individuals who were trapped in a system that did not allow them to flourish.” She says decades of seeing bright young children kept from their dreams led to a slow buildup of “distilled discontent” within the community.

This discontent was made worse by the discovery that the school’s well, which also served many houses in the area, was contaminated. Some trustees and some parents lobbied for more funds to fix up the school, but a larger number was beginning to favour integration.

That same year, 1964, also saw Ontario inaugurate its first black MPP, Leonard Braithwaite, who in his first speech as an MPP called for the striking down of the 1850 segregated schools legislation. His remarks drew attention from newspapers and the Ontario government took the law off the books.

Soon the trustees and parents of S.S. #11 heard that the Essex County school board was planning to close most of its one-room rural schools and divert those students to a large new elementary school — but not S.S. #11— and they suspected that the white trustees of the county school board were planning to leave the S.S. #11 students out of the changes. The trustees denied this, but the dispute was picked up by major newspapers.

Some members of the local black community got together with George and Alvin McCurdy of Amherstburg to form an advocacy group called the South Essex Coloured Citizens’ Association. The group then lobbied to have S.S. #11 closed and the students sent to the new, integrated elementary school. By then the majority of the local black community had come to support integration. And in 1965, S.S. #11 finally closed.

Couzzens was accepted into the consolidated school system and continued teaching until her retirement about 10 years later. Larkin eventually retired after 30 years as a teacher-librarian. She served three terms as a director with the North American Black Historical Museum, and still volunteers there. A few years ago she collaborated on a project to develop primary and secondary school curriculum for the teaching of African-Canadian history.

Even though she stopped school earlier than she would have liked, Johnson says she’s learned as much outside of school as she did in school. She mentions Mac Simpson and his wife, Betty, the founders of the museum in Amherstburg. “Before he came along, I didn’t know I had any history,” she says. She’s hopeful that young people from her community will also take an interest in this history. Larkin agrees: “Someone with no past has no pride. They have nothing on which to build a foundation.”