Share this page

By Helen Dolik

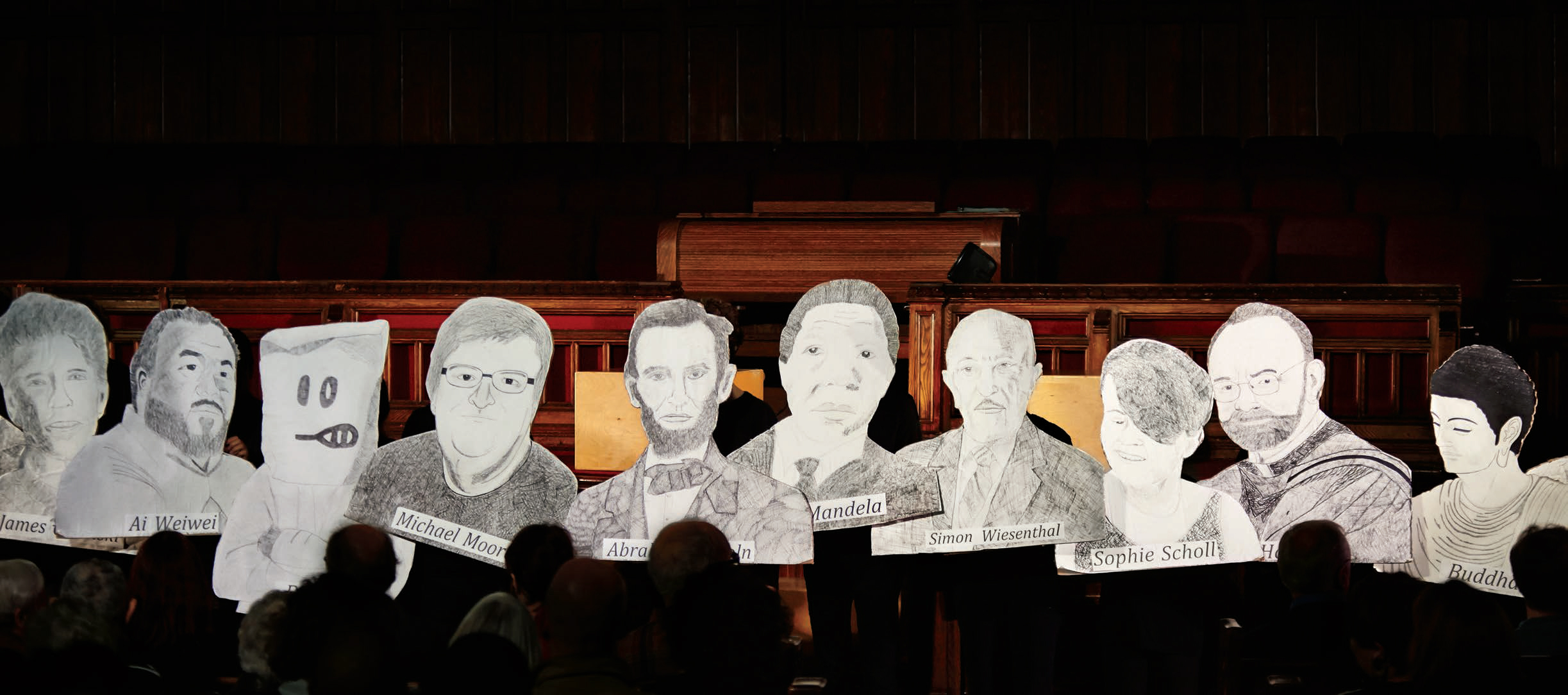

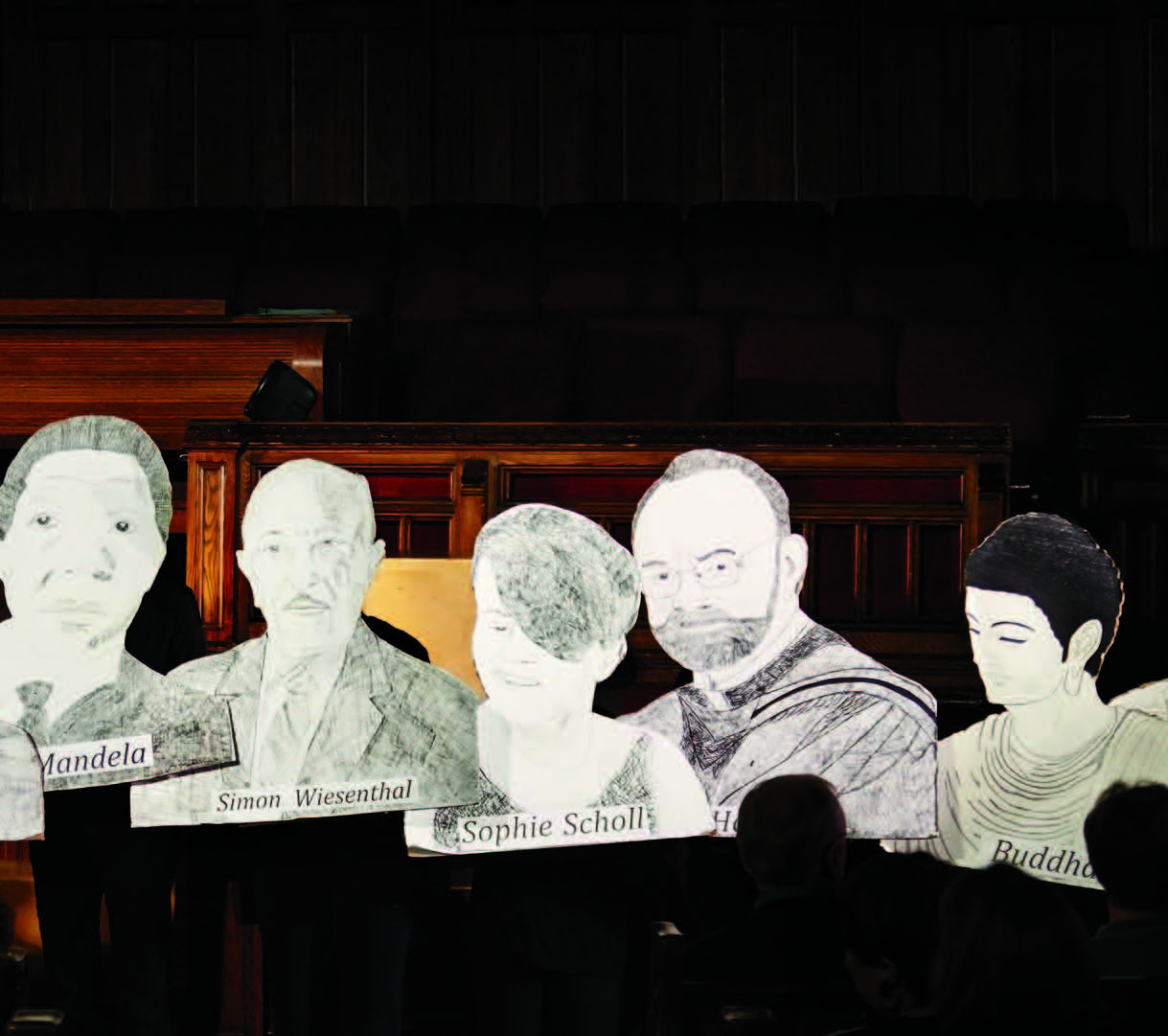

Photo: Matthew Liteplo

It’s April 2014 and the Grade 8 students of East Alternative School of Toronto (E.A.S.T.), dressed in black, march onto the stage at the Metropolitan Community Church in downtown Toronto carrying huge portraits of individuals who have made a difference in this world. The cardboard heads of Abraham Lincoln, Nelson Mandela, Roméo Dallaire, Jackie Robinson and Malala Yousafzai, to name just a few, sail into view. John Mayer’s song “Waiting on the World to Change” plays softly in the background.

One by one the students step forward and recite a quotation from their chosen hero: “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. Abraham Lincoln.” “Courage was not the absence of fear. Nelson Mandela.” “I shook hands with the devil. Roméo Dallaire.”

Drawing a crowd of 600 people, the annual performance of Courageous Voices has begun. In the next hour, the students will bring these cardboard portraits to life. They will become their heroes.

“A Grade 8 cast? People dismiss it until they come and see it. Then they never miss it,” says Lynn Heath, OCT, the E.A.S.T. teacher who co-ordinates the annual production.

E.A.S.T. is a Grade 7/8 alternative school in Toronto that integrates the arts throughout the curriculum. The teaching of social justice is a school-wide initiative, and Courageous Voices grew from that philosophy.

The Courageous Voices performance is just one way Ontario Certified Teachers are teaching students about social justice. Other OCTs use storytelling, books by diverse authors — including from their students’ culture of origin — and a theory of knowledge course.

Social justice can take on many meanings. Oxforddictionaries.com defines it as “justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society.” As part of the College’s Standards of Practice for the Teaching Profession, members promote and participate in the creation of collaborative, safe and supportive learning communities.

At E.A.S.T., Heath says social justice means an awareness of the world, of the inequities in the world and the power structure of the world — good and bad. “It’s a global understanding of what is going on in the world in terms of justice.”

Courageous Voices is based on Joseph Campbell’s book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In Grade 8, students look at his definition of a hero, conduct research and pick someone to study. They then write a persuasive essay explaining why this person is a hero based on Campbell’s criteria. The class decides whether the person truly is a hero.

Students create a life-size portrait of their chosen hero, collect his or her famous quotes and become that person. The heroes are separated into groups according to theme. For example, the 2014 performance included Be the Change, We Shall Not Forget and Women of the Revolution. A play with scenes is created for the various groups, where the heroes talk to one another.

“It becomes this unbelievably moving final production that grounds the students in what some of the social justice pioneers in our human history have done,” Heath says. “The goal for them is to have these words in their head, and they do. These are the most beautiful words ever written and spoken in history.”

Living heroes are invited to attend performances. Gay spiritual leader Brent Hawkes, humanitarian doctor James Orbinski, environmentalist and activist Julia Butterfly Hill and a Terry Fox family representative have attended performances. Barack Obama turned them down a few years ago but the American president did send E.A.S.T. a nice letter.

“Too often when you’re teaching social justice, you get mired in despair,” Heath says. “The things that are happening in the world are pretty awful. We thought ‘this has to change’ and that’s part of Courageous Voices. The line that comes up is ‘You’ve got to give them hope.’ You don’t want them to see the world as a bleak place.”

Heath assesses students throughout the project, including the formal essay, a speech and the drama part. “We have students who are absolutely quiet, who have not found their voice at all, and who find their voice through this,” she says.

Afterwards, students write a personal reflection. “Their responses bring me to tears because they say things like ‘I found my voice.’ That’s how I measure success here,” Heath says.

While a drama production is one way to teach students about social justice, a Guelph teacher uses storytelling as a tool.

“[The performance] becomes this unbelievable moving final production that grounds the students in what some of the social justice pioneers have done.”

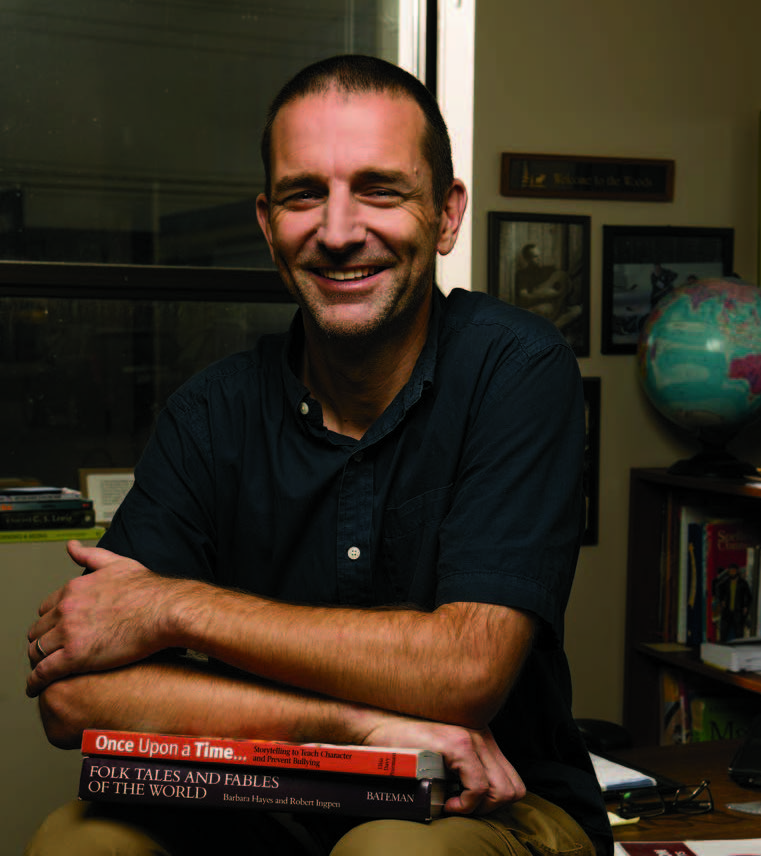

Brad Woods, OCT, is a Section 23 elementary school teacher with the Upper Grand District School Board as well as a professional storyteller. Section 23 educational programs serve students with a range of social and emotional needs, and are offered in various locations outside the regular classroom.

Woods has been telling stories for 16 years and has performed in venues across North America and in the United Kingdom. He is a member of the Great Wooden Trio, a group that combines song, story and music, and presented at a storytelling and social justice symposium in April at the Toronto Storytelling Festival 2015.

Storytelling and social justice are not separate, Woods says; one is a direct pathway to the other. “It’s a way to open our eyes, ears, minds and hearts to other ideas, other perspectives and other solutions,” he explains. “It is an empowering strategy that allows us to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes. It helps us understand those around us and, as a result, it helps us understand ourselves. The art of storytelling can play an active role in bringing about social justice.”

Storytelling and social justice are not separate; one is a direct pathway to the other.

When used well, one brings about the other, he says. “If I had to choose between lectures, rules, laws and stories, I would pick stories every time. Stories are engaging, educational, empowering, enlightening and entertaining.”

Woods shares folk tales and personal stories in the classroom. He reads folk tales to his students and they respond to the stories.

“The beauty of the folk tale as a tool for social justice is that the main character almost always learns a lesson that makes him or her a better person,” he explains. “They become stronger, wiser or more equipped to survive, thrive and potentially lead in their community. These characters are also usually an unlikely hero, such as a young boy, an old woman, a servant or a beggar. Ultimately, this is what social justice is all about.”

Woods provides a few examples of folk tales he uses in the classroom: The Crow and the Nightingale, a story about who to listen to and who not to listen to; The Stonecutter, a Japanese legend about accepting who you are; and The Wooden Sword, a story about living in the moment and not getting hung up on reputations. He’s also written stories about identity, acceptance and perspective.

Woods and his students share personal stories in small groups at “check-in time” in the mornings. They talk about their previous evening.

“If I said we’re going to have a storytelling session, I think the students would be nervous. If we role model, they start telling their stories,” he says. “It’s amazing some of the conversations that grow out of that.

“You’re connecting with them. You’re building relationships, which is essentially a big part of social justice — recognizing their uniqueness, their preferences and what’s important to them.”

Woods has access to hundreds of tales on his bookshelves or inside his brain. “We all do,” he says. “When you start considering all the stories you know, that were told to you, we all have heaps of them.”

He views social justice as self-defining. “It’s like asking ‘Why is it important to teach common sense? Why is it important to teach kindness?’ Social justice is being fair to people. It’s about being just with society and treating people well. If we can’t do that, nothing we learn in the classroom is even important.”

The passionate storyteller hopes the social justice concepts seep through the stories he shares with students. “When they leave here at 3 p.m., when they leave here on Friday, and when they leave here in June, I want them to take those things with them,” Woods says.

At the École secondaire Jeunes sans frontières in Brampton in the Conseil scolaire Viamonde, Julie Godin Morrison, OCT, relied on myriad teaching methods to raise awareness of social justice in her French and English classes.

The multicultural school has many students from Africa and the Caribbean, or their parents were born outside Canada. Godin Morrison taught French and English in the regular and International Baccalaureate programs at the school for five years. In September 2014, she took on a new position at the school board as a teacher-facilitator in its safe and accepting schools initiative.

“Teachers play a key role in the school community … It’s important that they show leadership, both during and after school hours, because they can have a positive or negative influence on students’ commitment to social justice.”

“Even though most people associate social justice with citizenship curriculum, at the Conseil scolaire Viamonde, we try to incorporate it into every course,” Godin Morrison explains. “The curriculum for language courses is very broad, so it was easy for me to explore social justice themes related to diversity and equity. The goal is to develop the students’ critical thinking and foster an openness to the world through the learning of two languages.” To help students understand social justice and the concepts of diversity and equity, Godin Morrison used several books in class from the African diaspora and elsewhere, with works as diverse as: Une vie de boy by Ferdinand Oyono (a Cameroonian author), Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe (a Nigerian author), The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros (a Mexican/American author) and La mémoire de l’eau by Ying Chen (a Chinese-Canadian author). She also devoted time to Martinique authors Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire, and to the autobiographies of African-American writers Langston Hughes, Lorraine Hansberry, Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X.

Students were inspired to contribute in class by being exposed to writers from their culture of origin. “In general, students demonstrated a keen interest in participating in the course content by sharing their experiences,” Godin Morrison says. “For example, the historical novel Things Fall Apart, which retraces the history of colonization, inspired some students to bring cultural symbols of their native village to class, such as a traditional strategy game and works of art.” This stimulated discussion and boosted the young students’ language learning, while opening their eyes to the world and developing their critical thinking.

“Ideally, we should take our class’s demographic profile into account in our teaching methods. By including authors from African cultures, I captured the interest of African-Canadian students and allowed others to discover Africa while maintaining my students’ interest in language learning and social justice.”

Godin Morrison used the theory of knowledge course, which she also taught, to help students understand the importance of language in the study of knowledge and how it can influence the way we see things. “The language we speak can lead us to make judgments about others,” she says. “As a practical exercise, I asked students to choose a character from a book studied in class and assign that character qualifiers. This allowed them to see that language can have major social consequences and that they should not be intimidated by language and intolerance.”

Godin Morrison believes young people are eager to become socially engaged outside their immediate circle and that’s why it’s important to teach students about social justice.

“This is why we must help them channel their energy in this direction,” she says. “Teachers play a key role in the school community. They must lead by example and act as role models for young people. It’s important that teachers show leadership, both during and after school hours, because they can have a positive or negative influence on students’ commitment to social justice.”

Back at E.A.S.T., Heath brings out her school’s yearbook and shows the pages where students and parents have provided glowing comments about the impact of Courageous Voices. Students tell Heath that it’s the best project they’ve ever done.

“It ends the students’ time at E.A.S.T. on this real high where they’re going out feeling they are important people who have made a difference and will continue to make a difference. Parents can see the change in their children,” she says.

—With files from Annik Chalifour

Ontario students deserve schools that are safe, inclusive and accepting places to learn, and the province is working toward that goal.

The Accepting Schools Act, or Bill 13, requires schools and school boards to prevent bullying, including cyberbullying, by taking preventative measures, issuing tougher consequences, and supporting students who want to promote understanding and respect for all. For example, boards must have policies about equity and inclusive education, the prevention of bullying and progressive discipline.

The Act promotes a “positive school climate that is inclusive and accepting of all pupils, including pupils of any race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status, family status or disability.”

The legislation, which amends the Education Act, was passed in June 2012. It is part of the government’s strategies to help create safe and accepting schools in Ontario — a necessary condition for student success.

Different types of social justice initiatives abound in the province and across the globe. Here are a few: