Share this page

By John Hoffman

Illustration: Katie Carey

When Andrew Wilton, OCT, started teaching in 1988, he saw very few women in senior positions at his board. “Almost all the people at the top were males,” he says. Now, as Wilton approaches the latter stages of his career, almost three out of five OCT members with supervisory qualifications are female. Wilton himself has worked under various female administrators and superintendents, and three female directors of education, one of whom happened to be African-Canadian.

Judy Philpot, a retired teacher, has one very strong memory from the day she applied for her first teaching job in Toronto in 1969. She thought she was going for a personal interview, but it turned out to be a “mass thing,” as she put it. “People were lined up down the street. Most of us were women, but my perception was that they came out and selected all the men and interviewed them first. And then, before they got to me, they came out again and said they’d filled all the positions.”

Philpot, who did manage to land a job that year, guesses that the school board was looking for male elementary teachers and was giving them priority in the hiring process. Women have always outnumbered men in elementary teaching. And, now, almost 50 years after Philpot started teaching, the number of male elementary teachers appears to be shrinking — despite increasing gender equity in many aspects of the teaching profession.

These two personal observation snapshots speak to a few of the key themes emerging from Professionally Speaking’s examination of the changing demographics of the teaching profession in Ontario. Many things have changed over the past 20 or so years, and others, like the age of teachers and where they are located, remain relatively unchanged. However, as the data reported here will show, there are two areas where interesting shifts are taking place: gender balance and racial diversity.

Women have outnumbered men in teaching for many years, particularly in elementary schools, and the trend toward a higher proportion of female teachers continues. In 2014/15 there were four times as many women as men teaching in elementary schools. In secondary school teaching women also outnumber men.

A similar trend can be seen across Canada. According to data from Statistics Canada’s household survey, 84 per cent of Canadian elementary teachers and 59 per cent of secondary teachers were female in 2011. (Statistics Canada data may not be comparable to the Ministry of Education data.)

Some education stakeholders have expressed concern about the relative lack of male teachers in elementary schools. In Narrowing the Gender Gap: Attracting Men to Teaching, a College report published in 2004, the authors noted that both “men and women are needed to ensure excellence in teaching,” and that “there is a discernible need to address a growing gender gap through the implementation of policies and plans to attract men to the teaching profession.”

Doug Gosse, professor of education at Nipissing University agrees. In 2011, he co-authored a paper with fellow professor Mike Parr, based on a survey of 223 male teachers. “Over 90 per cent of our respondents felt that male teachers have unique qualities that are of value to students, often using familial metaphors like ‘father figure’ and ‘big brother,’” says Gosse. “Most also felt that men who want to teach early grades face barriers such as misleading perceptions about men who want to teach young children. About one in eight of our respondents said they had already been suspected of inappropriate contact with pupils.”

It’s also fair to say that the lack of men in elementary teaching may reflect a historical gender imbalance that goes back to the days when elementary teachers were paid considerably less than their secondary colleagues. And if the lack of male teachers in elementary schools is a problem, then most Western countries have a bigger problem than Canada. Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development shows that, in 2015, Canada actually had a higher proportion of male elementary teachers than all other Western countries with comparable female labour force participation rates.

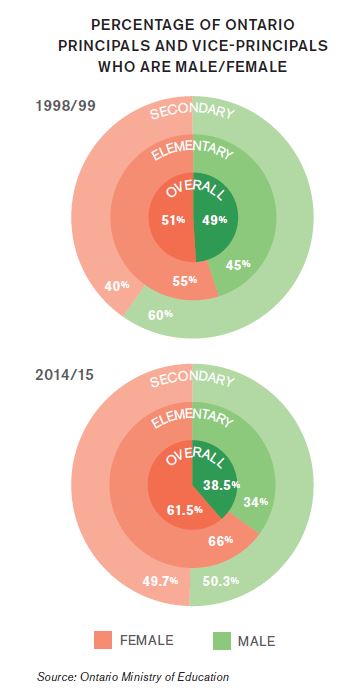

At the other end of the gender equity spectrum, there has been a steady rise in the proportion of principals and supervisory officers who are women.

In 1998, female principals and vice-principals slightly outnumbered their male counterparts in Ontario elementary and secondary schools: 3,764 women versus 3,631 men. Since then, the proportion of women administrators has increased significantly to 62 per cent, although it does not yet match the proportion of women in teaching overall (72 per cent).

A similar trend can be seen in those who hold supervisory qualifications. College research tells us that in 1998, 57 per cent of Ontario College of Teacher members with supervisory qualifications were male. In 2016, those proportions were reversed, with 57 per cent of teachers with supervisory qualifications being female. And currently, almost half (34 out of 72) of Ontario’s directors of education are female compared to 26 per cent just five years ago.

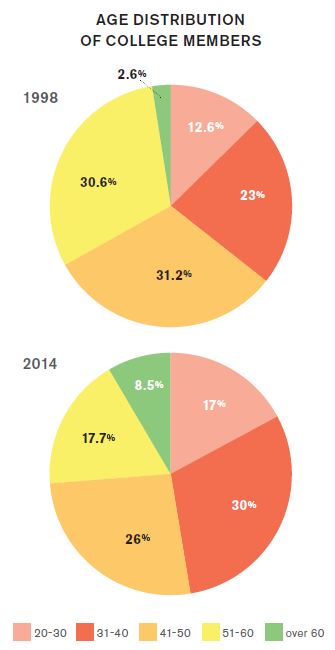

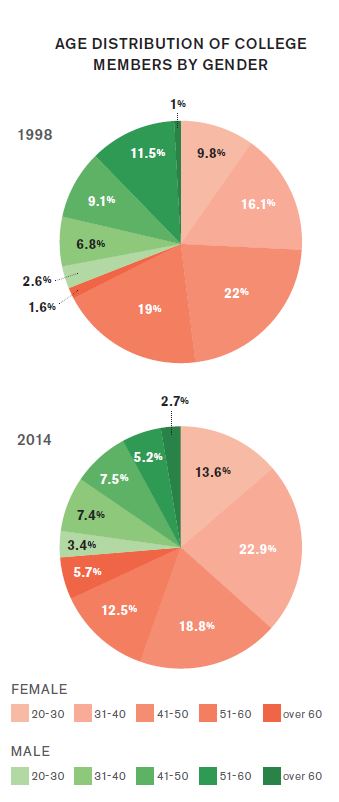

The average age of Ontario teachers (43), according to College statistics, has been more or less the same for the past 20 years. However, the proportions of teachers in various age groups are shifting. There are more younger teachers and fewer older ones in today’s classrooms compared to 1998. Close to half of Ontario’s teachers (47 per cent) were age 40 or younger in 2014/15 compared to just over one-third (35.6 per cent) in 1998/99. At the other end of the scale, almost one-third of Ontario teachers were between 50 and 60 in 1998 compared to less than one-fifth (17.7 per cent) in 2014.

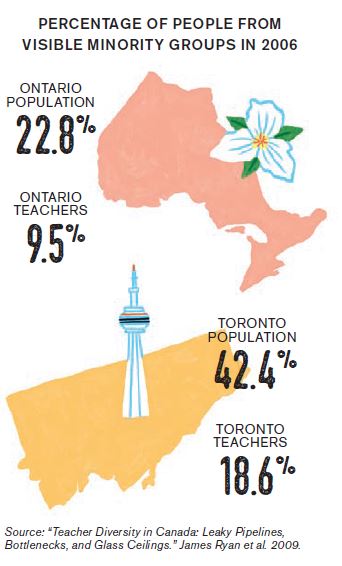

Although we could not find historical data that would indicate possible trends in diversity, it seems safe to say that the Ontario teaching workforce is more diverse than it was in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. However, it would also seem that the diversity of Ontario’s population is not proportionally reflected in the profession of teaching.

While most of Ontario’s teacher education programs have developed equity admissions policies, increasing the diversity of Ontario’s teachers continues to prove challenging. Ruth Childs, professor of education at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), led a study of her institution’s attempts to increase the proportion of underrepresented groups in its teacher education programs. “What we found was that our admissions policies and procedures were not disadvantaging any specific groups, which may have been the case in the past,” she says. “However, at the same time, making changes that would actually advantage underrepresented groups was difficult.”

Initiatives have also been undertaken to increase the number of Indigenous teachers working in Ontario schools, including Aboriginal Teacher Education Programs (ATEP), which provide a pathway to teacher certification for Indigenous individuals via a diploma, rather than a university degree, and newer Indigenous Bachelor of Education (IBE) programs at several universities including Brock, Lakehead and Trent.

Clearly such programs are needed. In 2002, the Minister’s National Working Group on Education noted that while Indigenous peoples comprised 2.3 per cent of Ontario’s population, only about 0.5 per cent of Ontario’s teaching force was Indigenous. However, while good data is not available on the proportion of Indigenous teachers in Ontario, Julian Kitchen, a professor in Brock University’s faculty of education, says ATEP and IBE programs have met modest success. “These programs have definitely made some difference in terms of increasing the number of Indigenous teachers in Ontario schools,” says Kitchen. “But there continue to be numerous challenges.” For example, some faculties set aside spaces for Indigenous teacher candidates but are unable to fill them. And, for various reasons, some Indigenous students face unique challenges that sometimes prevent them from completing their programs. “If the goal is to substantially increase the representation of Indigenous people teaching in Ontario schools, we will need more targeted programs like the ones that currently exist to help bring more Indigenous people into the profession,” says Kitchen.

It is important to note that many of the Indigenous teachers trained in Ontario are working as teachers, but not within the Ontario school system. As Lindsay Morcom, co-ordinator of the ATEP at the Queen’s University faculty of education points out, teachers trained in ATEPs often return to their home communities to work in First Nations schools, which are a federal rather than a provincial jurisdiction.

There is no doubt that we are in the midst of a demographic shift in the Ontario teaching profession. Joseph Picard, OCT, director of education with Conseil scolaire catholique Providence in southwestern Ontario, believes the makeup of the teaching profession in Ontario is moving in the right direction.

“When I started teaching 30 years ago, teachers were not a very diverse group,” says Picard. “Now, the population of teachers is more diverse, but in 20 years I would hope that the diversity in the teaching profession is more reflective of the diversity in our society. The difficulty for a French-language school board like ours is that to find more diverse teachers, we often have to recruit people from outside the province. And that comes with a whole set of challenges.” Picard is also concerned about the apparent steady drain of men from elementary schools. “I think we could do more to get the word out that teaching is a very rewarding profession in terms of personal and professional growth.”

According to Ontario College of Teachers statistics, between 1998 and 2003, 28 per cent of newly licensed Ontario teachers were trained outside of the province. That trend held fairly steady until 2009 when the numbers began to decline. Between 2011 and 2015 just 16.6 per cent of Ontario teachers were trained outside the province.

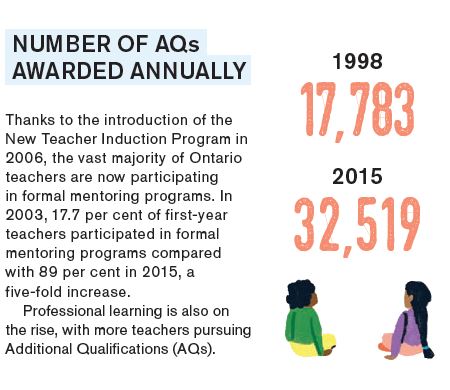

Thanks to the introduction of the New Teacher Induction Program in 2006, the vast majority of Ontario teachers are now participating in formal mentoring programs. In 2003, 17.7 per cent of first-year teachers participated in formal mentoring programs compared with 89 per cent in 2015, a five-fold increase. Professional learning is also on the rise, with more teachers pursuing Additional Qualifications (AQs).

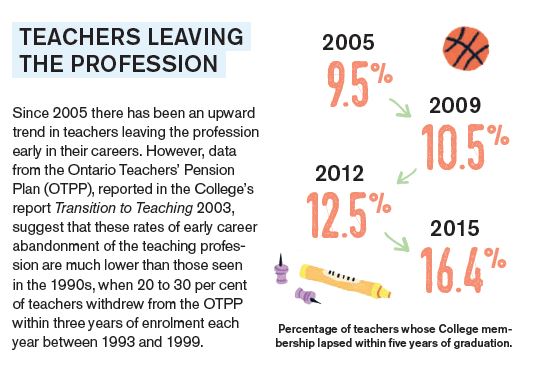

Since 2005 there has been an upward trend in teachers leaving the profession early in their careers. However, data from the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP), reported in the College’s report Transition to Teaching 2003, suggest that these rates of early career abandonment of the teaching profession are much lower than those seen in the 1990s, when 20 to 30 per cent of teachers withdrew from the OTPP within three years of enrolment each year between 1993 and 1999.