Share this page

By Jennifer Lewington

Photos: Matthew Liteplo

They come from afar as experienced teachers who leave home to write the next chapter of their professional careers in Ontario public schools. Professionally Speaking asked four Ontario Certified Teachers, born and trained abroad, to describe their adjustment to a new culture, unfamiliar pedagogy and professional development practices.

In 2003, on her first day as a supply teacher in the District School Board of Niagara, England-born Samantha Lengyel, OCT, knew she was no longer in her east London primary school: Ontario students and staff rose to sing the Canadian anthem. "We don't play the national anthem at school [in England] but it is the first thing that happens at school [here]," she notes.

She arrived in Canada in 2000, shortly after marrying her Canadian husband, Nick, a teacher with the Niagara board. Two years later, now a mother of one, she received her teaching credentials and began supply teaching in 2003.

Another difference Lengyel notes between the British and Ontario school system is Ontario doesn't use the English system of ministry inspectors who visit schools to assess student progress. "That was huge in my first year of teaching [in England], but it's not something that happens here."

During two years of teaching in London, Lengyel had access to a mentor and other professional development, as Ontario teachers do, but without the release time permitted here for lesson planning.

In 2007, after almost four years as a supply teacher, she received a permanent full-time position with the Niagara board and currently teaches Grade 3/4 at Prince of Wales Public School in St. Catharines, Ont. After teaching in two countries, Lengyel describes her professional growth as an evolution, steadily adding College-recognized subject qualifications since 2012. "What I was like at the beginning [of my career], compared to what I am now, has really changed a lot," she says. "You constantly have to adapt and change."

Newly married in 2014, Jamaica-born teacher Marlon Douglas, OCT, travelled to Fort Frances to visit his wife, also Jamaican, who was working for a long-term care home in the northwestern Ontario town. Unfamiliar with winter (average monthly snowfall in Fort Frances is 20 centimetres), Douglas decided "I can probably live with it" and moved to Ontario the following year.

A graduate of the University of Technology, Jamaica, in 2009, with a bachelor of education in technical vocational education and training, Douglas taught technical drawing and construction technology over six years on contract at various schools on the Caribbean island.

In Ontario, Douglas assumed his job search would echo that in Jamaica: apply directly to a school. Instead, he had to search postings listed by a district school board.

In December, 2015, he was hired as an education assistant for the Rainy River District School Board, assigned to Crossroads School, 22 kilometres west of Fort Frances, serving LaVallee Township and Naicatchewenin First Nation. "Switching from a foreign country was the best experience I have had in my entire career," he says, of his two years as an educational assistant - one year in a Grade 5/6 classroom and another in a student transition room at the school. "It was just the right thing for me to do to be introduced to the system ... it was a different culture, different background, different everything."

New to Indigenous traditions, he joined Crossroads students for his first ice-fishing trip. "Even though the students, the environment and the people are different [than in Jamaica], it is still the same principle: it is about the learning environment you have to create for that group of people."

As a new teacher in Jamaica, Douglas received informal mentoring. But in Ontario, he participated in the New Teacher Induction Program, a formal mentorship program run by the Ministry of Education and local school boards.

In 2017, after earning his teaching licence, he joined the Rainy River board as a supply teacher. Douglas recently landed a permanent three-year contract as a board-wide support teacher, visiting schools to assist classroom teachers with the science and technology curriculum.

After teaching French and German in high school for seven years in his home town of Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, Laurent Teinkeu Sieyapche, OCT, moved to Canada with his family in 2014. "I wanted to give my children the chance to grow up with the values of Canadian society," says the married father of two boys, five and three years old.

Teinkeu Sieyapche earned his education teaching credentials from the Université de Yaoundé 1, but enrolled in a teacher education program at the University of Ottawa to accelerate his career here, graduating with distinction in 2017.

In Yaoundé, he says it was "normal" to teach a classroom of 80 to 100 students. "There was a lack of infrastructure …and it was not easy to manage the students to be sure that everybody had a seat and a book for the course."

Last year, he joined the staff of École élémentaire Carrefour des Jeunes, a public French-language school in Brampton with Conseil scolaire Viamonde, teaching classes of about 20 students. "Here, I know the names of all the students and I also know the parents," he says.

In Cameroon, Teinkeu Sieyapche used a personal computer at home, but only a minority of Yaoundé schools had reliable electricity and internet access. He says a major difference between schools in Cameroon and Canada is the availability of resources for teachers working with students with special needs. "[In Ontario] if I don't have enough, I can call for help [from the board] or go online."

At Carrefour des Jeunes, Teinkeu Sieyapche taught gym, soccer and other sports, including hockey, a game he discovered when a friend here took him to a National Hockey League game between the Ottawa Senators and the Toronto Maple Leafs. "I was interested and curious to try this sport," he recalls, first practising on Rollerblades before playing with a puck and a stick.

Teinkeu Sieyapche taught hockey to his students in the gym using sticks and a puck. "They loved it," he says. This year, in addition to teaching arts and physical education to first- and second-year students at Ottawa's École élémentaire et secondaire publique Maurice-Lapointe, with the Conseil des écoles publiques de l'Est de l'Ontario, he is a soccer coach to Grade 5 and 6 students at the school.

Born in apartheid-era South Africa to a family whose forebears came from India, Michael Naicker, OCT, acquired his education, including teacher training, at segregated, Indian-only schools. "I was going to an Indian school and the African children I would play with would be in a separate school and the White children in the village had their own school," says Naicker, born in KwaZulu-Natal.

After earning a bachelor of education at the University of the Western Cape in 1995, he pursued a master of education, with a scholarship, from the University of Leeds in England.

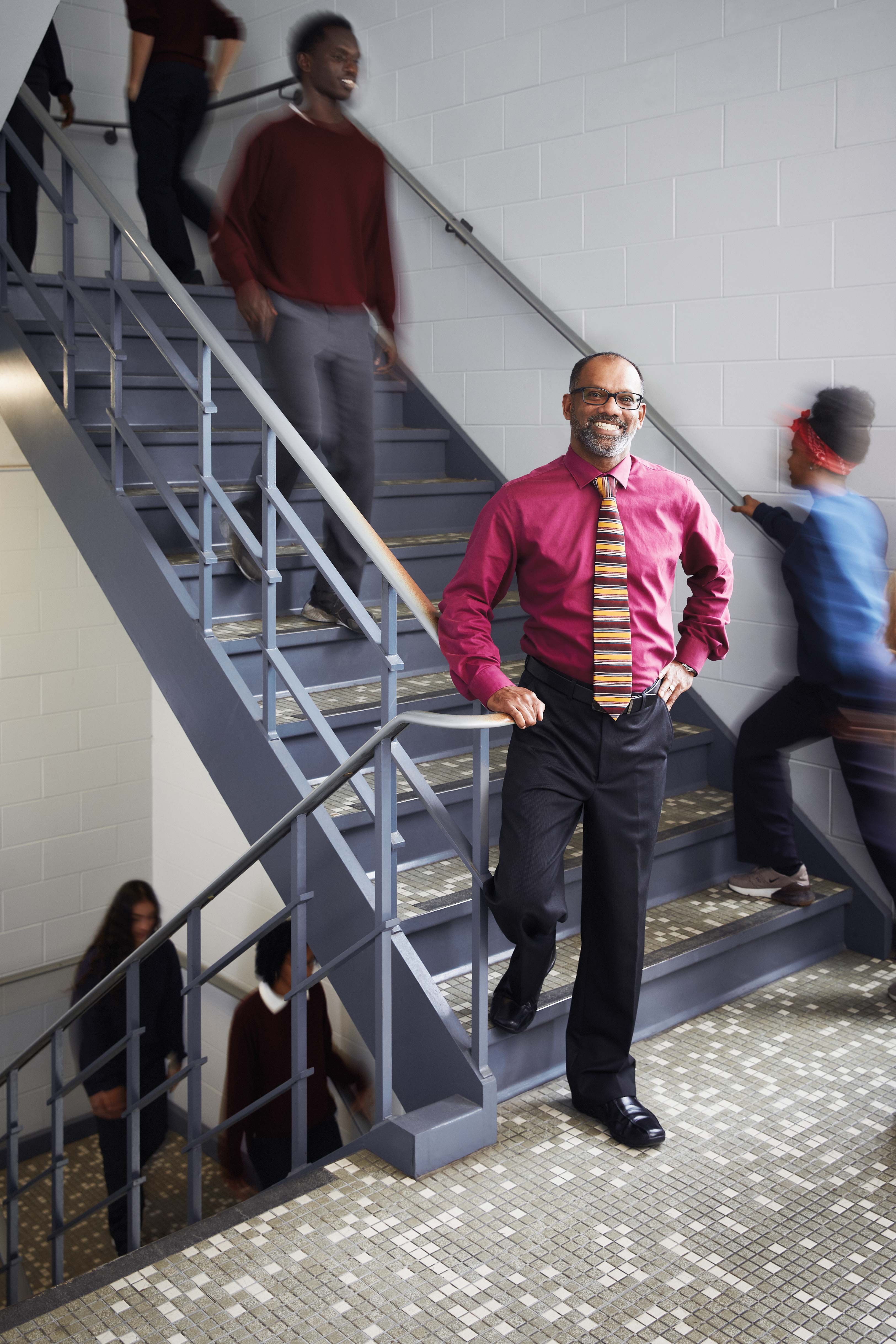

Today, Naicker is a vice-principal at Catholic Central High School with the Windsor-Essex Catholic District School Board. "We are a multiracial school full of immigrants," he states proudly. "I treat them all with respect."

Looking back on his career in South Africa, where he taught every grade up to 12, he says Ontario schools take a progressive approach to struggling students. South African high school students who fail one of two compulsory language subjects (English or Afrikaans) have to repeat the entire academic year but Ontario students only repeat the failed subject. "I like the Canadian system where you are not punishing kids for the entire year."

In 2002, troubled by escalating violence in post-apartheid South Africa, Naicker chose Canada for the next stage of his teaching career, in part on recommendations from several South African friends who had moved here. While on a visit to Ontario in the early 2000s, he concluded, "This is a nice place; I can raise my children here."

Arriving in 2005, Naicker volunteered at a local school in Windsor and obtained his teaching licence from the College three years later.

After working as a supply teacher with the Windsor-Essex board, and later as an adult high school instructor, he joined Catholic Central High School in 2007.

One early obstacle for Naicker was the language of a school system that used course codes and other acronyms, not subject names familiar to him in South Africa. "You crossed the ocean, you have a master's degree, you can do this," he says, ruefully.

Naicker says computerized recordkeeping now facilitates his life as an administrator, compared to less sophisticated and "more labour intensive" systems used when he served as an acting principal in Cape Town.

Like other internationally trained teachers, Naicker says that despite country differences in education systems, one similarity looms large: "We all have the same vision: we want our children to succeed."

According to the College, internationally educated teachers represented 16.4 per cent of Ontario College Teachers in good standing in 2017. Excluding the United States, the proportion drops to 7.1 per cent. Australia, India, England and Scotland top the list of home countries of foreign-trained teachers who relocate to Ontario. But the province also attracts a significant number from Jamaica, Pakistan, Ukraine, Nigeria, Lebanon, the Russian Federation and the Philippines.