Share this page

Ontario Certified Teachers from across the province share their stories about how they use smart software and other tech tools to enhance student learning.

By Stefan Dubowski

Photos: Matthew Liteplo

Whether they’re using robots to teach teamwork or having students wear virtual reality (VR) headsets to learn about far-off places, teachers are using technology to excellent effect in the classroom. Get inspired to try some new tech tricks with your students.

Andrew Dobbie, OCT, a Grade 6 teacher at Centennial Senior Public School in Brampton, Ont., was already working with students to refurbish old computers acquired through Renewed Computer Technology (RCT; rcto.ca) — a non-profit, charitable organization that collects, refurbishes and redistributes donated desktops and laptops for use in schools. But he wanted to take his tech teaching to an even higher level.

Dobbie devised an activity to raise the bar: working in pairs, the students would watch a YouTube video on how to install the Linux operating system on the computers. (Linux enables older computers to run faster.) Then they’d write out the steps to create a how-to document for others to use. Along the way, they practise analysis, critical thinking and writing, all while participating in a larger Earth-friendly and fiscally prudent project to reduce e-waste (diverting old computers from the landfill) and save money — a lotof money. Dobbie figures over the years he’s partnered with RCT, he and his students — alongside other teachers and classes he has connected with — have helped save schools some $1.4 million, funds the school boards would have spent to buy new computers instead. “It’s cost-effective, great for the environment, and the children learn,” he says of his work.

Enzo Ciardelli, OCT, a teacher at George L. Armstrong Elementary School in Hamilton, Ont., has students learn about shape characteristics as part of the math curriculum. But he wanted to find a way to get them excited about what can be an unexciting lesson for some. So he connected that must-do learning with computer coding: students use Scratch (learn-to-code software) to program the shapes onscreen, requiring the students to understand how measurements like length and angle come together to form, say, a square or a rectangle.

“It’s interesting that when they’re doing it, they really don’t want your help,” Ciardelli says. Aside from his showing them how the program works and how to draw lines, “they want to solve it themselves.” And it isn’t long before the students rise to greater challenges: can you draw a hexagon? An octagon? The children also develop logic — learning, for instance, that it’s more efficient to write “Go forward, turn right, repeat four times,” than write “Go forward, turn right” four times separately. He has the students write their code on paper and hang their work on the wall for others to use, too. “They compete to be the first one to get it done, but they’re also happy to share it.” He recommends having students program in pairs, noting that many professional programmers work that way. “If one student is not as [confident] in their skills, then the other can help.”

Marisa Leclerc, OCT, wanted to motivate her Grade 7 and 8 students at École catholique Val-des-Bois in Marathon, Ont., to learn both inside the classroom and while away for hockey tournaments and other activities. She started using OneNote Class Notebook, an online program with features like individual student notebooks and an assignment board. Her class can use their laptops to view assignments, take notes and even work together in the program’s collaboration space for group projects, whether they’re at school or on the road. Two goals, one program: OneNote helps keep students interested. “Students like to work on laptops, so right there your motivation is through the roof,” she says. It also enables mobile homework.

Leclerc finds the program especially handy for group work since students can exchange notes in the collaboration space. And from her teacher account, she can see which student contributed which comments or ideas to the group project, making it easier for her to assess student engagement and participation. “Start small,” she advises other teachers who might want to introduce this kind of system. “Don’t show them everything all at once, because they will forget.”

When he heard computer company Lenovo was running a contest to award schools with virtual reality (VR) headsets, Nicholas McCowan, OCT, knew he had to enter. This science teacher at Jean Vanier Catholic Secondary School in Toronto felt his students would really benefit from the technology. Most of them are English language learners who struggle to make their voices heard. “When you’re new to a country it’s intimidating to speak in a foreign language in a foreign environment,” he says. He believed the VR headsets would give the students a new way to interact, communicate and express themselves. Lenovo did too, awarding Jean Vanier with 10 VR headsets.

McCowan got straight to work linking technology to the high school science curriculum. He developed an activity in which students don the headsets and connect to Google Expeditions — a VR-content library — to explore different environments. They use the voice-typing function in Google Docs to record and transcribe their thoughts as they make their way through deserts, rainforests and other biomes. “One thing I had to do was push them to be a little more expressive,” he says, noting that the students spent a lot of time simply saying “Whoa!” It all began as a way to support student voice, but it has gone further: inspired by their VR experiences, some of the teens started fundraising to rebuild coral reefs in Australia.

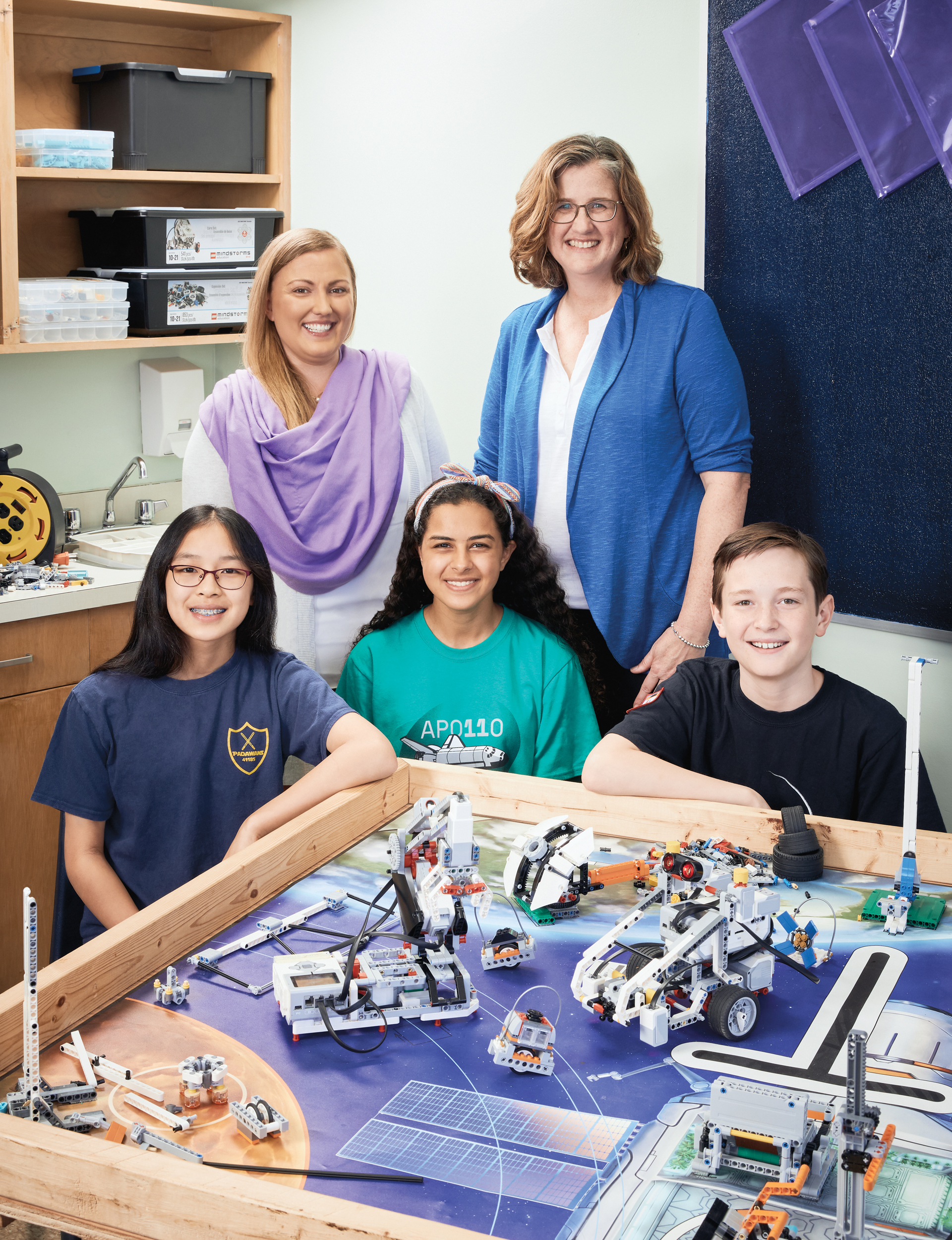

Always searching for new ways to develop students’ inquisitiveness and perseverance, Sari McDowell, OCT, and Shauna Nelson, OCT, may have landed on the perfect activity: a tournament involving robots and Lego. These teachers at Doon Public School in Kitchener, Ont., help organize teams to participate in FIRST Robotics Canada’s FIRST Lego League tournament, an event in which students build Lego robots and program them to get through a series of challenges (firstroboticscanada.org/fll).

The teachers start each fall getting the teams together and collecting the material required, including the robot-building kit and all the pieces needed to put together a practice mat, with the same challenges they’ll face during competition day in December. And whenever they can — during breaks, over lunch or after school — the students learn to program the bots and develop their presentations for the inquiry portion of the competition. (For the December 2018 event, the teams had to present solutions to a real-world problem related to living and working in space.) “It’s nice to give them an authentic task where there are goals to work toward,” McDowell says. “They definitely develop leadership skills and how to work as a team,” Nelson says.