Share this page

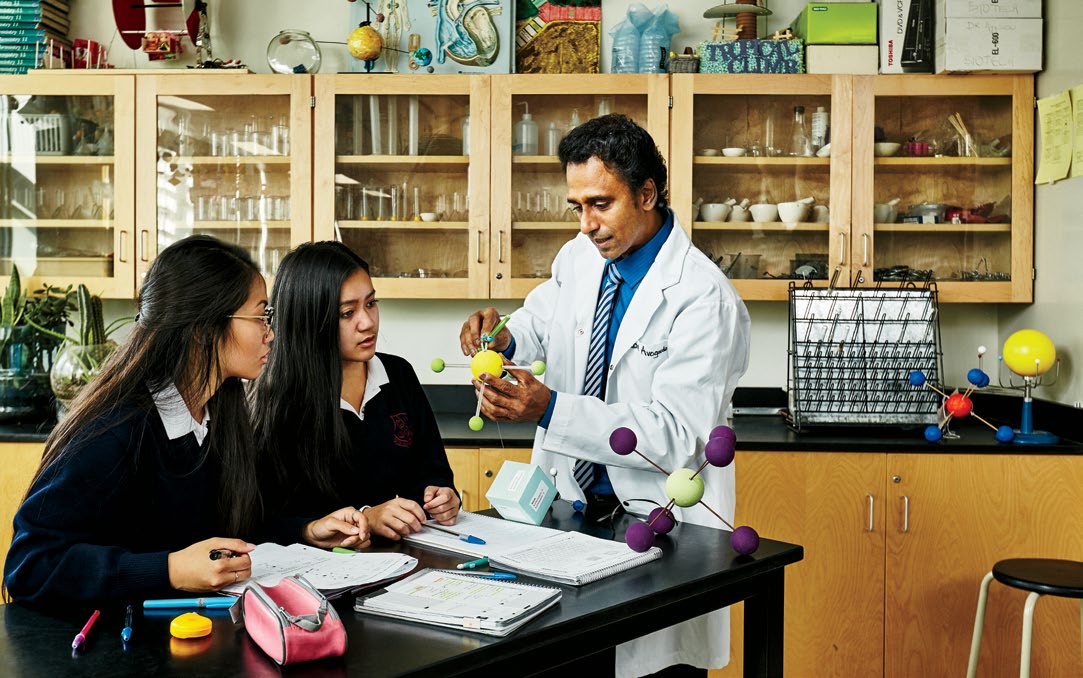

When it comes to science, Gabriel Ayyavoo, OCT, breathes new life into teaching high school biology and his professional practice.

By Trish Snyder

Photos: Markian Lozowchuk

To view our Great Teaching video archive, visit Professionally Speaking.

Gabriel Ayyavoo, OCT, may head the science department at Toronto’s Notre Dame High School for girls, but he’s not above using a little drama to teach Grade 12 biology. He hoists a rack of test tubes holding four clear colourless solutions, each containing mystery ingredients. “Yesterday we learned how to test for simple sugars with Benedict’s reagent,” Ayyavoo tells his class. “Today, I’ve mixed a bunch of chemicals together into these four solutions. It’s your job to figure out which ones contain monosaccharides.”

Intrigued at the challenge, the young women quickly get to work, dividing into lab groups, sketching observation charts, fetching test tubes and bottles of reagent. Ayyavoo pulls his white lab coat on and scurries around the classroom. He grins his approval at hearing one team counting aloud as every drop of reagent trickles into a solution. He praises others with a “Good technique!” for remembering to set aside a control and mixing their solutions properly. Suspense builds as the girls hover over hotplates to watch the liquids change colour. If everyone performs the experiment correctly, they should end up with two orange solutions and two blue ones.

“Based on the colour, who thinks solution A contains sugar?” Ayyavoo asks. As hands spring up, he grips the mystery ingredient (a bottle of corn syrup) like a trophy. “Glucose, yes, excellent!” He reveals other secret components like a meat tenderizer and sucrose. Although most nailed the experiment, two groups manage to turn a couple of their solutions pink and purple. Where some might see a misstep, Ayyavoo sees it as a chuckle and a learning opportunity. “This is good,” he tells them. “It reminds us that even if a scientific test appears to be easy, we still have to be careful.”

Careful — but not because Gabriel Ayyavoo is a perfectionist or because his students are obsessed with acing their next exam, but because this isn’t just about testing for sugar — it’s about using science to solve real-life problems. For 25 years, Ayyavoo has converted average teenagers into high school scientists through an innovative assignment he developed called Scientific Investigative Projects (SIPs). These are not your average bristol-board presentations: the girls devise and conduct their own experiments at bona fide labs in top facilities such as the Hospital for Sick Children and the University of Toronto. Over the years, his students have investigated just about everything: one girl determined that waterproof eyeliner is more likely to cause eye infections than the regular formulas; another discovered a new antibacterial agent from moth dung, while a third studied the impact of broccoli on breast cancer cells.

With astonishing frequency, his students have been rewarded for their efforts: by presenting their findings around the world, they have won 250-odd science fair medals, collected hefty university scholarships and cash awards totalling more than $250,000. Along the way, Ayyavoo managed to earn his PhD in education along with a heap of teaching prizes, including the 2013 Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence. “He challenges students to think critically about what they’re learning and about the world around them,” says colleague and French teacher Rosemary Paniccia, OCT. “In an age where everything is standardized, Gabriel has the courage to be different in the classroom.”

To declare Ayyavoo a fan of experiential learning would be like describing the Grand Canyon as a hole in the ground. He unpacks scientific concepts with experiments, excursions and hands-on tasks the same way a coach trains players in a sport. Can you imagine teaching soccer by reading books? “Doing science is how you understand science!” he says. That means he might start a lesson on the merits of microinvertebrates in the classroom, but then he’ll march everyone over to a nearby ravine to scoop them out of the mud. In fact, in 2010, six of his Notre Dame students collected water samples from Toronto’s Don River and used the micro-organisms to study the water conditions. They published the results and then presented their paper at the University of Malaysia in 2011.

It’s hard not to get into science when Ayyavoo makes the subject so entertaining. Strict teaching methods were the norm when he was a boy growing up in Singapore. Priests lectured, and the children listened. Since his own enthusiasm for science sprouted from observing animals at the park and asking his mom about plants, he took a different approach as a Sunday school teacher — he used collaborative activities and games to get children bent on learning. “I saw students learning more about religion on Sunday than at regular school,” he recalls.

Ayyavoo is the antithesis of his childhood teachers. He asks and welcomes questions — even from the student who once dared him to taste a chocolate-covered cricket she brought to class. Science and physics teacher Lisette Santos-DeSousa, OCT, says his collaborative approach encourages students to think for themselves. “I believe that there are two types of teachers: the sage on the stage and the guide on the side. Gabe is the latter. He’ll say, ‘Let’s figure it out, let’s look at this together.’ It’s a different level of communication that’s much more collegial.”

Since his students are so interested in technology (he likes to call them “digital natives”), he’s been a pioneer in using IT as a learning tool in the classroom. Take videos, for example. He’ll lay out the foundation of a topic in class and then send students home to do additional research online and make a video to simplify a particular concept. (One girl’s movie about viruses was as gripping as a Hollywood trailer.) In a sense, Ayyavoo flips the classroom on its head: “They post the video, others see it, and then we discuss it together in class. Isn’t this better than me standing at the front talking?”

He relies on online discussions to support different learning styles. The educational hub Edmodo.com, for instance, allows students to apply what they’ve learned by prompting responses to articles and questions Ayyavoo posts. He covers everything from the labelling of genetically modified foods at the supermarket to the environmental hazards of pharmaceutical waste. This method encourages those who might stay quiet in class to contribute freely on screen and incites healthy debates that help students to connect the proverbial dots between what they’re studying at school and what’s happening around them.

The girls apply their budding scientific skills by completing annual SIPs. It’s not by fluke that the assignments are student-centred: Ayyavoo knows that when teenagers explore what interests them — from nutrition to transportation to women’s health — it fuels their desire to learn. He coaches them through a rigorous scientific process that starts with forming a question they want to investigate, and then developing a hypothesis and predicting their results. They design their own experiment trials by combing through journals; hunting for research papers to see what investigation methods and apparatus other scientists use. He meets with them regularly to review their progress and to help scale back any overly ambitious projects, or change gears if something doesn’t prove feasible.

To get them plugged into the scientific community, Ayyavoo asks students to submit their finished proposals to dozens of researchers — seeking permission to perform their trial in a working laboratory. (His classroom is well stocked with gear, but even he can’t crack open a catalogue to place an order for breast cancer cells.) When a student who’s sent out 40 emails gets that crucial one that says “yes,” bystanders can expect to witness jumping for joy in the hallway. Even in her French class, Paniccia overhears the girls discussing their science projects. Seeing that their work has value feeds their curiosity — this is why Ayyavoo believes SIPs are worth the effort, and why he hopes to join a university’s education faculty to spread the word to other science teachers. “These girls are spending their weekends doing research and they’re so excited to talk about it,” he says. “That’s when I know I’ve got them hooked on science!”

After conducting their trials, students make observations, provide conclusions and write a full report. They celebrate their learning at their school science fair, and many present at larger science competitions. Instead of letting all that impressive research get thrown into the recycling bin when the fairs end, Ayyavoo founded a science club called DameDetectives (bit.ly/1sYR6ky). Students act like the board of a scientific journal, reviewing peer submissions and publishing the best ones to inspire others to pursue science.

For her SIP last year, Rhea, a Grade 12 student at Notre Dame, tapped into her love of international development: knowing that hundreds of millions of people worldwide lack access to clean water, she investigated an algae that neutralizes harmful bacteria in untreated water. She won a Canada-Wide Science Fair award in 2013 — an invitation to a youth symposium in Australia, where she attended a presentation by a Nobel Prize winner, Skyped with scientists in Geneva and networked with young people, who like her are using science to change the world. “It was life-transforming,” says her mother Hyacinth Fernandes, OCT. “Rhea has seen that if she puts in the work she can pursue her dreams — and she learned all of this just by doing a science project. Dr. Ayyavoo really is opening doors for these girls.”

The teacher who is featured in this department has been recognized with a national teaching award.

Through the Ministry of Education-funded Teacher Learning and Leadership Program, Gabriel Ayyavoo, OCT, is learning how to better use iPads and laptops to create lessons and assess student work, not to mention improve student collaboration and communication skills. Here’s a sampling of some of the award-winning science teacher’s favourite educational apps that he uses regularly and encourages his students to explore in and outside of the lab:

Context: (bcontext.com)

Share pictures that are layered with voiceovers with this interactive whiteboard.

YouTube Capture: (bit.ly/1n2WqDO)

Record yourself on video; then edit, crop and share it via YouTube right from your device.

Keynote: (bit.ly/1yv5mTP)

Create presentations with photos, videos, transitions and animated charts in a snap. Since the iCloud is integrated, students can use this tool to collaborate on projects.

Socrative: (socrative.com)

Design an interactive activity on any tablet, phone or laptop. Through its real-time questioning and instant result tabulation, you can gauge your students’ comprehension level.

BrainPOP: (brainpop.com)

Watch animated content on science, social studies, English and more; then leverage the app’s quizzes, games, movies and activity pages to gauge students’ retention levels.

Science360 for iPad: (bit.ly/1twlrbH)

Check out visuals and videos from the National Science Foundation’s library.

TED: (bit.ly/1keZMg2)

Access thousands of inspiring talks about science issues and other global issues.