Share this page

By Stefan Dubowski

Photos: Matthew Liteplo

From smartphones to laptops, from classroom apps to board-wide software, the range of technologies available to teachers is broad — perhaps overwhelmingly so. As a professional, you need to consider not only the spectrum of solutions, but also how hardware, software, apps and games affect student learning and the way you go about your work as an educator. So how do you assess these high-tech options and how might you make the best use of them?

To help answer those questions, we interviewed six teachers from across the province who are taking technology in the classroom to the next level. Read on for inspiring case studies of teachers turning to 3D printing, digital portfolios and other tools to motivate students and improve learning outcomes.

While teaching Grade 6 last year at St. Gabriel School in Ottawa, Jennifer King, OCT, gave her students access to technology to facilitate group work. She also gave them lessons in constructive collaboration. The students thrived on the software and the instruction.

They were studying invasive species such as zebra mussels and giant hogweed. The learners worked in groups of four or five to consider ways to keep the largely unwanted invaders from destroying Ontario’s natural environment. They used web-based collaborative tools, specifically Google Apps for Education (google.com/edu), to collect and develop their findings. Apps for Education includes software for word processing (Google Docs), presentations (Google Slides) and data storage (Google Drive).

Document management was the key in order for students to work together. They could see from the information in Drive when a document was added. They could also see who in their group was contributing to the documents — who was providing new information and who was making helpful comments. And everyone could see who wasn’t contributing. That caused trouble. At one point during the project, some of the students complained to King about the laggards. Rather than mediate, she taught them constructive feedback. “They learned to respond to an issue like that respectfully,” such as telling a team member that the group values their input and needs him or her to play a bigger role, she says.

That perspective empowered the students, enabling them to handle a group-work crisis later on: members of one team wanted to leave because they couldn’t support the ideas of their compatriots. Using their new communication skills, they discussed the matter and amicably agreed to split the team. “The conversations they had were more adult-like than the ones I’ve been involved in, in similar circumstances,” King says.

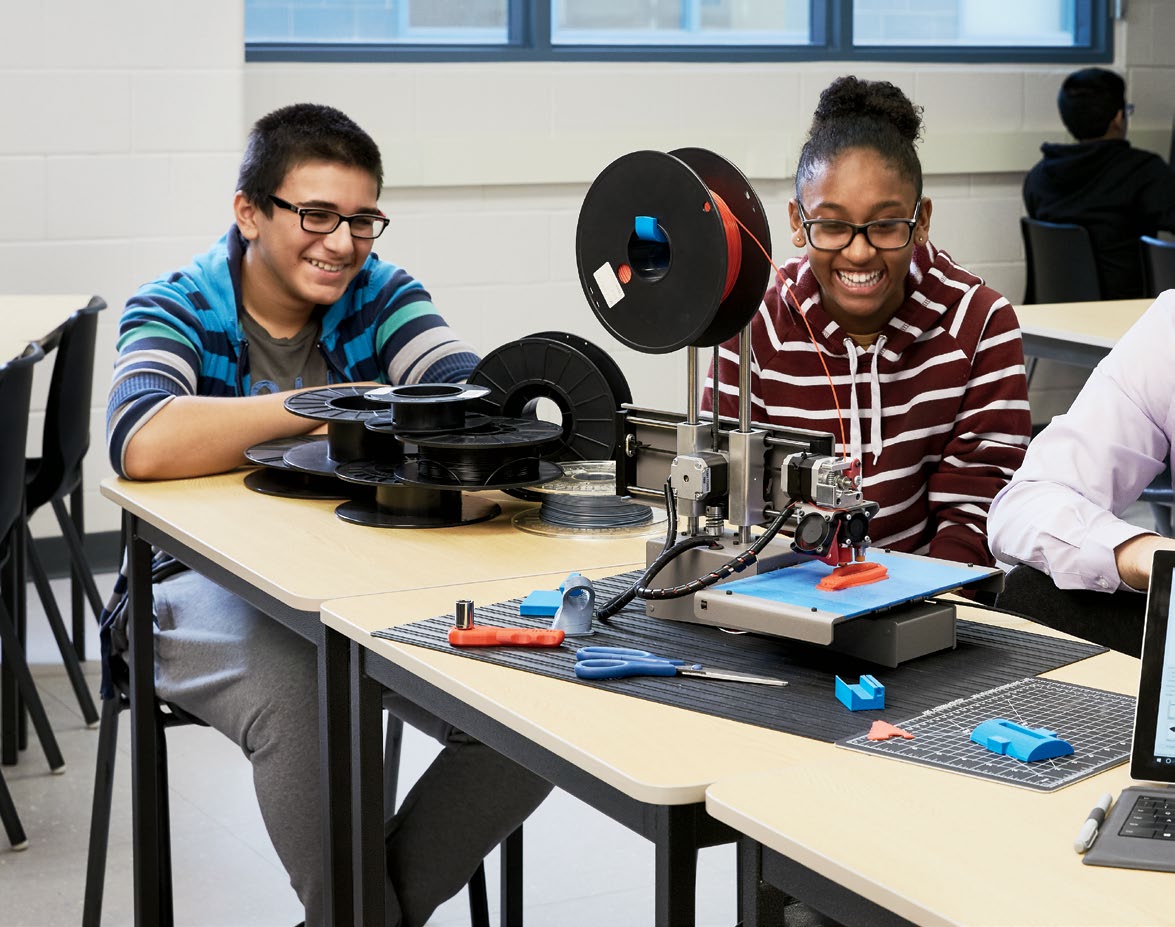

David Del Gobbo, OCT, was on a mission to engage and inspire his Grade 9 Special Education students at Stephen Lewis Secondary School in Mississauga. To that end, he introduced a tough activity for the teens: take a real-world problem and solve it through 3D printing.

The students were asked to tackle a straightforward challenge presented by classmates, such as create a replacement handle for a pair of scissors. They had to research the matter, brainstorm ideas and evaluate each other’s progress as they designed their solutions.

Along the way, they learned to use free 3D design software: Tinkercad (tinkercad.com, see p. 18 for more) and 123D Design (123dapp.com), both by software company Autodesk.

“All of the items created had to be designed almost completely from scratch,” Del Gobbo says. “One of the temptations with 3D printing is to simply reprint other people’s designs.”

Once the designs were peer-reviewed and modified based on feedback, the students were given the chance to make their work truly real using a 3D printer.

The project was enriching. The students honed their research, critical-thinking and problem-solving skills. They also improved their math skills, since they had to make precise measurements to design their objects. And they learned the importance of assessment and improvement. “Sometimes the physical act of handling their object brings up more issues for them to solve,” Del Gobbo says. “A certain edge might be too sharp or a certain part may be too small in a certain dimension. So they often make additional tweaks and print out another version.”

The project brought education into the realm of reality. As Del Gobbo put it, “The sheer satisfaction that students have when they see their object being printed, and eventually hold it in their hands, is immense. It’s a huge incentive for them to persevere even when they hit roadblocks.”

As for the teacher, Del Gobbo proved the power of the practical. By giving students control over the problem-solving process, and by focusing their efforts on a real-world challenge, the teenagers worked more diligently than they would have on more abstract tasks. To check out his lesson plans go to docs.com/delgobbo.

“The sheer satisfaction that students have when they see their object being printed, and eventually hold it in their hands, is immense.” —David Del Gobbo, OCT

Marcie Lewis, OCT, sought a better way to teach her Grade 6 students the art of self-reflection at Ridley College in St. Catharines. There had to be some method to improve their ability to review and make sense of their work, to see how far they’ve come, to scrutinize their strengths and weaknesses.

Lewis introduced video journaling as a solution. She used it during a six-week multidisciplinary assignment in which the youngsters identified and researched responses to real-world problems, such as child labour, lack of mental health care in developing countries, and the spread of infectious diseases. In the research phase of their projects, the students would use school-provided Apple laptops to record videos of themselves answering a number of probing questions, such as: How would you summarize your topic? What are you most proud of with respect to your work so far? What have you learned about yourself?

The results were eye opening — for the students and the teacher. The technology suited the children. They had an easier time articulating themselves on video than they did in writing, making the video journals eminently practical as they tackled challenging topics. Lewis also got to know her students better, especially those who wouldn’t necessarily speak up during class discussions. “Sometimes in a classroom, they’re not as comfortable sharing with the whole group, but they still have lots to say,” she points out. And the students benefited from reviewing their videos to see how their thinking had changed over the course of the project, driving home the idea that through research and study, people learn and grow.

Lewis has tips for other teachers who want to use video journals: find a quiet place for the students to record their reflections so they can concentrate; have them keep their videos relatively short, perhaps no longer than three minutes, so they’re forced to focus; and use a file-sharing service that can handle large files, like Dropbox (dropbox.com) or Google Drive (google.com/drive), so students can share their videos with you — without clogging your email inbox.

Andrée Levasseur, OCT, felt sure that her Grade 6 math students at École élémentaire et secondaire publique Maurice-Lapointe in Ottawa would be more engaged if she taught differently. Specifically, she wanted to give the youngsters more time during class for exercises. “Otherwise the homework is done at home and when they need help the teacher isn’t there,” she says.

So Levasseur and her colleagues overhauled their lessons, incorporating online videos and more in-class practice.

The teachers start with the videos. They record and upload their own content to YouTube, usually a video in which they give a lesson in geometry, measurement or another aspect of the curriculum. During class, the students use school-provided laptops or tablets to watch the content. Then they spend most of the class working on activities that the teachers have designed to help them practise what they learned.

Levasseur says the method gives the teachers more time to respond to students’ questions instead of lecturing. The students benefit, too. They learn at their own pace, since they can watch the videos as often as they need in order to understand the lesson. And if they require help, they can get it immediately.

So far, this non-traditional system is working well. The students are “engaged and motivated,” she says. “And they appreciate the time in class to work on their activities.”

In the future, Levasseur plans to have students create their own videos. “Sometimes it’s better when it’s taught by a peer,” she says. “I think they relate to the lessons better. And they really seem to like it.”

Levasseur suggests that it’s important to use technology only when and where it makes sense. “I believe technology must not serve as a substitution for pencil-and-paper tasks. We have to aim to use it to transform teaching.”

Walk into one of John Rodgers’ Grade 9 to 12 math classes at Bruce Peninsula District School, and you may be expected to pull out your smartphone and get ready for a math-quiz battle. This OCT in Lion’s Head, Ont., often kicks off with a session of GameShow, an interactive app developed by Canadian software company Knowledgehook (knowledgehook.com/gameshow). Over the course of about 10 minutes and five to 12 questions, the students are tested on their understanding of math concepts based on the Ontario curriculum. Questions pop up on the screens of their smartphones and tablets; the students enter their answers, score points and compete to see who is most knowledgeable. (There is also a non-competitive option.)

“I tend to leave it in competitive mode,” Rodgers says. Players have just a few seconds to answer each question and, when the match is done, they get to see who are the top scorers. Does that competition make students anxious about their math knowledge — or lack thereof? Not in Rodgers’ experience. “Nobody seems to be really upset if they’re not number one,” he says. “And it generates a lot of energy and excitement.”

GameShow is an example of a student-response program in which children respond to whatever’s happening in the game, app or software. While researching technologies for the classroom, Rodgers and his colleagues found that students get more out of this sort of system than, say, video-recording software or grade-management programs. With student-response technologies, “you can generate a math-talk community in your classroom,” he points out. “They talk about the options. You get a lot of mileage out of something like that.”

Discussion is one of the main ways for students to become engaged in a subject, which is why Rodgers doesn’t fret if a student doesn’t have his or her own smartphone or tablet with which to play the game. He regularly has the learners work in teams anyway, so they share a device. “Sometimes that’s a better way to organize it because you’re definitely going to get that conversation.”

Rodgers believes that educational technology has come a long way, indicating that in the past, there was more hype than substance. “Having technology in the classroom is finally making sense.”

Regardless of the technology employed for learning purposes, OCTs are encouraged to consult the Ontario College of Teachers’ professional advisory, Use of Electronic Communication and Social Media, to help guide their professional judgment.

Last year, students at Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati Catholic School in Toronto collected their best work in digital portfolios. Then they got ready to reflect and present.

Specifically, the children saved their assignments and homework in their individual Google Drive (google.com/drive) folders. Then the students curated their work, identifying what they felt were the most important elements, including feedback from peers and teachers. From there, the learners created student-led conferences to be delivered midyear — parent-teacher interviews that were “flipped” in that the students explained their progress and what they thought they needed to work on.

“The students ran the show,” says Maddalena Shipton, OCT, a Grade 1 to 8 French as a Second Language teacher, who partnered on the project with Grade 5 teacher Daniele Motanaro, OCT. In addition to Google Drive, they used Google Slides (google.com/slides) to make the presentations, including charts to describe where they started and what they’d achieved. They used the Screencastify feature on Slides to record the presentation with a voice-over so parents who couldn’t attend the conference would be able to watch the presentation on their own time.

At the end of the year, the students went even further: they built on their student-led conferences using any additional material in their portfolios to create passage presentations in which the children explained why they should move on to the next grade. They used Adobe Spark (spark.adobe.com) to create videos to summarize their points. The videos included QR codes that, when scanned with a smartphone, led to a feedback form where parents and teachers could add their comments.

These projects, the student-led conferences and the passage presentations, tied in with a school-wide, student-empowerment initiative dubbed #ICANyet, which saw youngsters combine digital portfolios with a motivating idea: even if you can’t do something today, keep trying and you’ll succeed.

“[That concept] helped students appreciate that learning is a journey and that they are on the right path to success — even when it’s not a straight one.”

Tina Zita, OCT, knows very well that technology has transformed the educational process for many teachers and students. But she also knows that in one particular way, not much has changed.

An instructional technology resource teacher with the Peel District School Board and previously a kindergarten to Grade 5 computer teacher, Zita has seen technology become commonplace in the classroom. However, “we’re still having to have conversations about its worth,” she says.

That’s been the situation for a while. Some argue that technology in class is a distraction and that students don’t learn core subjects such as math, history and language — only how to use computers.

To help set the record straight, Zita suggests that teachers need to emphasize education when talking to people who worry about the effect that technology is having on students. “I think we need to [move] the conversation away from technology to the learning goal,” she says. “Technology is just a tool that gives students access to information.”

As a tool, technology may involve any number of activities. Whether it’s apps students can use to communicate more effectively or video games that they can play to learn key concepts. Whatever form technology takes, it is only truly useful when teachers and students apply it to specific educational purposes.