Share this page

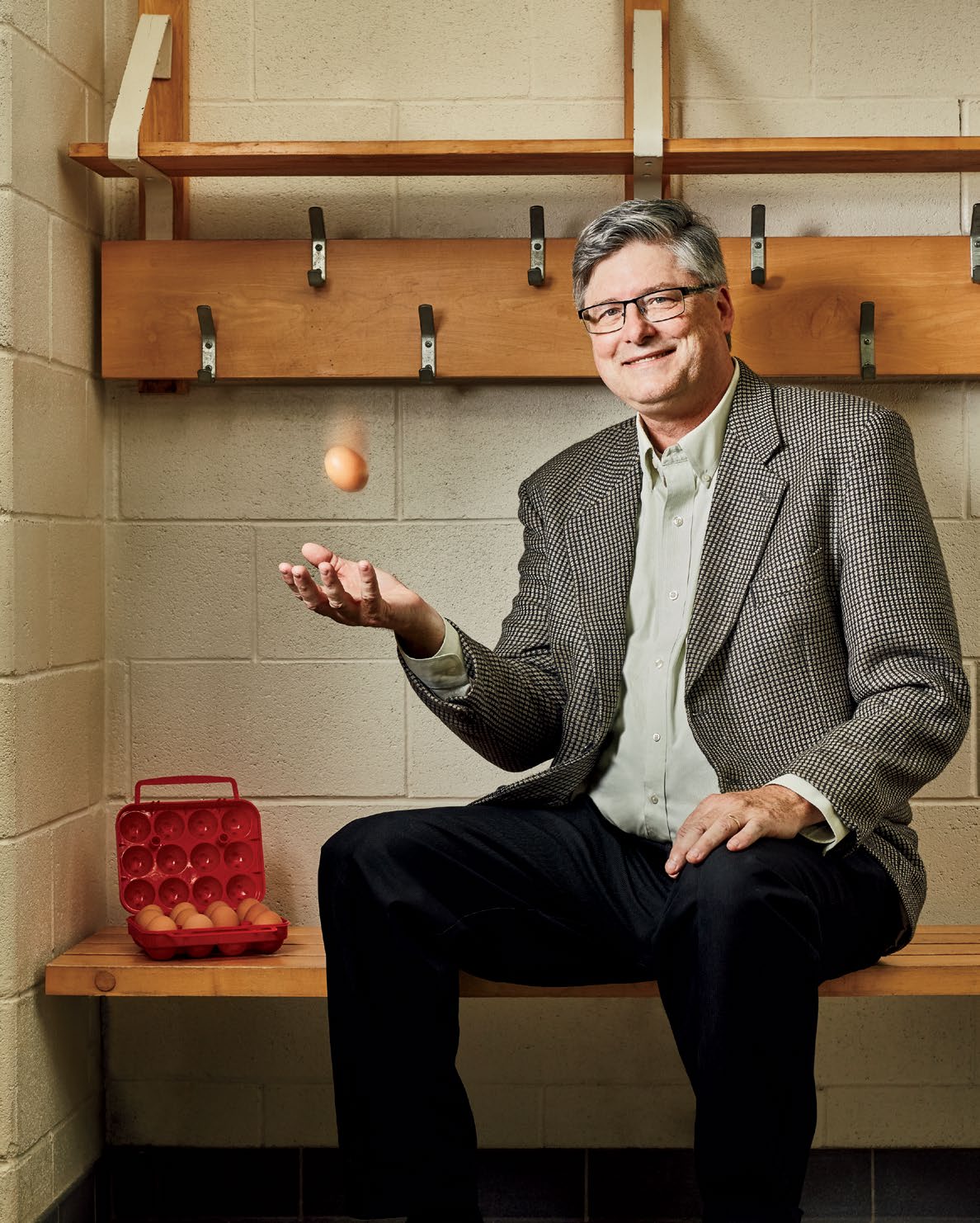

Steven Revington, OCT, lays the groundwork for his Authentic Learning model at the elementary level by cracking it wide open with real-world applications.

By Trish Snyder

Photos: Markian Lozowchuk

To view our Great Teaching video archive, visit oct-oeeo.ca/w2qkmg

Tough to say who’s more excited on a muggy June morning at Emily Carr Public School in London, Ont. — Steven Revington, OCT, or his Grade 4 students. They’re on the verge of conducting a live experiment before hundreds of spectators — including students, family, staff, politicians and even a camera crew.

Working in pairs, they’ve applied lessons on gravity and drag to the design of a package or “capsule” that they’ve constructed to protect a raw egg during a four-storey fall. A London Hydro employee was invited to test the class’s pods by dropping each one from a cherry picker hovering above the unforgiving schoolyard pavement. Dressed in white lab coats, the young scientists head outside to wait, well, on eggshells, as the hydro worker propels skyward with their colourful projects.

The materials are decidedly low-tech but they’ve got all the features you’d want in an aircraft. In fact, Revington initiated his first drop in 1985 after discovering that NASA had perfected its Mars landing capsule design in the 1950s by securing eggs in prototype spacecraft, then tossing them off helicopters.

Many of the handmade pods are loaded with cotton balls, foam peanuts or bulging, air-filled plastic packs. One duo braced their box for impact by attaching cardboard strips folded like an accordion. Another pair topped a baby wipes container with cardboard rotors shaped like maple keys. Just as the first capsule is about to be tested, a fellow teacher enlisted to emcee the event pauses the blasting music and begins the countdown: “Five, four, three, two, one!”

Spectators gasp as the first box drops and rolls. Revington eyes his stopwatch, announces the flight time — which students record on clipboards — and then carefully peers inside the package. The creators hoist a “Yea” cardboard sign to indicate their egg’s safe arrival, and the yard erupts with applause. The next capsule lands with a splat, shattering the beer cup shock absorbers and its fragile cargo. The audience cheers as the youngsters sheepishly flash a “Yuck” sign along with 500-watt grins. When the final pod — wrapped in pool noodles — lands with a springy bounce, a petite scientist literally jumps for joy.

It’s no wonder Revington has stalled his retirement for four years: unbridled enthusiasm is a typical reaction whenever he dreams up events that transform his students into rocket scientists, artists or music video producers. Inspired by brain research that shows children are more motivated and engaged when they learn by doing, the 32-year teaching veteran pioneered an educational model called Authentic Learning (authenticlearning.weebly.com) that plunges students into different roles to complete tasks with real-world applications.

The approach has earned him awards from TV Ontario and Western University. In 2015, he won a Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence and was one of three Canadians (selected from 5,000 nominations) to become one of the Top 50 finalists for the Global Teacher Prize, education’s answer to the Nobel Prize.

“I have never met a teacher who has been as intentional, effective or committed to meeting the learning and social-emotional needs of his students,” says Colin King, psychologist and co-ordinator of Psychological Services for the Thames Valley board. “Steve’s Authentic Learning model has engaged even the most reluctant students — [as well as] those with significant learning difficulties — in a manner that connects them to meaningful, real-life learning.”

For Revington, authentic learning is richest when students are called upon to solve a genuine problem with a tangible, useful product. “The idea is to prepare them for life in the most authentic, simulated way we can,” he says. Enter the egg drop. It’s one thing to tell students that astronauts needed to find ways to take care of expensive space equipment. It’s another when children learn about responsibility by “parenting” a raw egg for a week, then figure out how to protect it by playing with air resistance, impact and recoil — the same kind of thinking that goes into designing stronger packaging or safer hockey equipment.

The class is still buzzing post-drop, when it’s time to return inside to review the data. The students compare their times and draw flight patterns in the air with their fingers — straight down or a little curvy. It doesn’t take long for someone to answer when Revington asks if anyone sees a connection between flight times and patterns. “The capsules that went straight down went faster. Those with more curves have more drag and went slower,” says one girl. “That’s right!” the teacher says, and they’re off again chattering about the best crashes. Revington knows better than to fight it when children are so excited about what they’re learning that they can’t stop talking about it. “Let’s get your snacks a little early today,” he says. “You can have a social moment to talk about today’s event.”

Since this teacher is also a parent who knows little ones love pretending — from pulling on firefighter costumes to acting like bakers — he immerses them in the learning process by encouraging role-playing. First, the students get into character by dressing appropriately for the task. “I found that their focus, motivation and productivity increase dramatically when they wear lab coats and clip-on project clearance badges,” Revington says. Second, everyone slips into a different role during group work. If teams are building a tower, one child is the designated foreman, another plays accountant and another steps in as safety regulator. “They get to see that there’s a variety of skill sets needed to do the various jobs,” he says.

Revington believes learning deepens when you involve the greater community. After developing a passion for Australia when he taught down under for a year, the now-retired teacher presented Aboriginal myths and explained the spiritual significance of the country’s central region, where Uluru/Ayers Rock is found, to his students back home. He had the class spread out on the carpet to create authentic Dreamtime paintings, distinguished by earthy colours and dotted figures. He wondered what locals back in Australia would think of his students’ artwork, then made a few calls to find out: he sent their projects to Australia to be assessed by local Aboriginal artists. The pros were impressed with how well the students had connected with their land and techniques — four of the paintings were even framed and displayed in an outback police station. Seeing that their work had value to others made a greater impact than the highest grade or shiniest star sticker. “The expectations grow and the quality rises when you prepare something for the community,” Revington says.

Authentic learning events emphasize process, not content, by providing opportunities to make memorable personal connections with the world. Revington’s classes explore ancient history by choosing a Roman tradesperson and consulting real-life experts to create a product or tool of that trade. One boy visited a local custom guitar-builder and constructed a lyre while a girl travelled more than 100 kilometres to learn glass-blowing from an artisan. He says those interactions infinitely improve the quality of the final products and, because each learning journey is personal, the lessons stick. Finally, the class mounts a “living museum” open house, transforming their desks into market stalls, dressing in period costumes and pretending to sell their wares to visiting students, staff and parents. “It’s no longer enough to dispense content — a kid can find anything on his iPhone,” Revington says. “I try to be the architect who brings minds together. That’s the core of the human experience. It’s something you cannot do on a smartphone.”

Revington is never too busy orchestrating multi-layered learning events to tune into the needs of individual students. He made a deal with one girl who had an anxiety disorder — the moment she felt panic rising, she’d make a little “T” with her hands to signal she needed to retreat to the hall and collect herself, to avoid melting down in front of her peers. It was a window of opportunity she’d never been offered before — she used it once.

As soon as Michelle Schaap’s son, Wesley, had a taste of Mr. Revington’s next-level activities, she no longer had to fight to get him to school (her daughter was previously in Revington’s class). Together, with his classmates, Wesley helped to remake a music video by the band Empire of the Sun. Students used green screens, made costumes, filmed at a nearby museum, had the footage edited by neighbouring high school film students, then rolled out a red carpet for a gala and public screening.

It’s the kind of learning experience that leaves students with goosebumps and memories — a powerful way to stoke their fire for learning. “His approach goes beyond fun facts glued on bristol board, which gave my kids a drive to learn at a different pace,” says Schaap. “Mr. Revington showed my children how much they can accomplish. He has a real gift.”

The OCT featured in this department has been recognized with a national teaching award and exemplifies the high standards of practice to which the College holds the teaching profession.

Steven Revington, OCT, nurtures teamwork to maximize co-operation during learning experiences that mimic real life. Here’s how:

Personal Attention

First, he motivates students individually by observing their strengths and weaknesses, as well as asking about their likes and dislikes. A boy who loves football but not reading? Revington will drop a football magazine on the child’s desk, then photograph him reading. “I look for ways to make success happen.”

Co-operative Activities

Coaching soccer and hockey teams in the past helped Revington amass a solid toolkit of corporate team-building activities. Here’s one: Each student stands with one finger out. The class must lower four metre sticks to the floor in teams of three to five without losing contact with the stick. The sticks inevitably float upward, not down, until the students figure out they need one leader, lots of followers and plenty of communication.

Special Days

Revington rewards great teamwork by wrapping the day’s lessons around a theme. On Halloween, students sit in a circle and take turns complimenting each other while they pass around a ball of yarn — making a spider web as the yarn unfurls. “They start to make a connection: ‘When I co-operate with my buddies, look what I can do.’”