|

By Tracy Morey

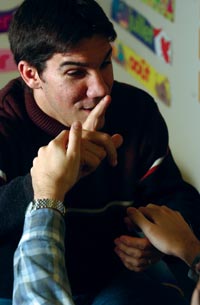

In two years, when

Patrick Deschatelets completes his degree, he'll be among the first deaf

francophones to become a teacher of the deaf in Ontario. Currently a teaching

assistant (TA) at the Centre Jules-Léger in Ottawa - the school

from which he graduated - Deschatelets helps teachers prepare materials

for elementary students and assists the teachers of an eight-year-old

deaf child and a 13-year-old who is blind and deaf.

"The older child has no communication, so we use tactile LSQ (Québec

sign language)," Deschatelets explains. "The younger child is

partially paralyzed and needs to express himself more, so I do gestures

and sign language words he can mimic. It is not possible to teach core

subjects to these students. The focus is on life skills, such as Braille

and sign language."

It's not frustrating, says Deschatelets, because he always sees progress

in the children's development. "Besides, I have a lot of patience

and I'm motivated to get them communicating with the world."

Once a week, he also teaches a night class in LSQ for parents. "It's

a rich and interesting language and parents are surprised at how involved

they get."

Students Teach

|

|

"Teaching

is the best way to use my communication skills..."

|

The TA, now in his

third year of work at the centre, meets with teachers monthly to plan

themes and discuss the visual materials required to get concepts across.

Deschatelets has learned a great deal from his young students. "I

explain something and often, they don't get it, so I have to take another

route. It's the exchange that gets them there. Following the child's way

of communicating is key to our success," says Deschatelets.

One of the major challenges Deschatelets and staff at Jules-Léger

face is having deaf children in residence, away from their families all

week. "It's a judgment call we make carefully. The deaf community

is so strong, and it has its own cultural values. Often, deaf children

can be more isolated and less communicative if they live at home, so we

feel the residential approach is best for most children," he says.

Deschatelets was born in Gatineau, across the river from Ottawa, and his

deafness wasn't diagnosed until he was 19 months old. A specialist suggested

he be trained in oralism, which involved having the toddler practise one

word aloud each week. Then his mother discovered the deaf community. "She

saw a church mass done in sign language and decided this was a much better

option," says Deschatelets.

Deschatelets commuted to Montreal for high school, played hockey and developed

a passion for alpine skiing. A severe bout with asthma laid him low when

he was 17 and he came home to Gatineau. Then his family discovered the

Centre Jules-Léger, a 30-minute drive away, and he has never looked

back.

To become a teaching assistant, Deschatelets picked up some university

credits, took a wide range of courses and work placements and completed

a deafness program at the University of Ottawa. "Teaching is the

best way to use my communication skills," says Deschatelets, "and

using language effectively is my goal."

Had to Volunteer

When her hyperactive

five-year-old reported he was the best-behaved child in his class, Manon

Fecteau concluded it must be a terribly lively class.

"I just had to volunteer to help," says the mother of three,

whose experience was a real asset in a room full of extra-high-energy

children. Fecteau went on to help out in other classes at the Academie

de la Moraine in Richmond Hill, which serves francophone students from

the Greater Toronto Area.

Four years after she'd done intensive volunteer work at the school, a

job posting appeared for a teaching assistant in the class where Fecteau

was helping. The unilingual francophone native of Montréal, who

had worked as a hairstylist, didn't apply because she "didn't have

the papers." Then the teacher she worked with suggested that Fecteau's

volunteer track record more than qualified her for the job.

Now into her second year as a TA, Fecteau works with double Grades 1/2

and 3/4, each of which has four or five children with behaviour problems.

While the teacher works with Grade 1, she may do reading with Grade 2,

with a special eye on those who have trouble concentrating. There are

only eight students in the Grade 3/4, so the four students with problems

"can work as a team." Fecteau's role is to assist the teacher,

organize class trips and materials and give specific help to individual

children.

Take Time to Listen

|

|

"...and

using language effectively is my goal."

|

It's an easier workload

than last year, when Fecteau was responsible for several children with

disruptive behaviour problems that required a lot of attention. "I'm

back to little cases, where the children's behaviour problems simply tend

to involve difficulty in groups. Though these students can disrupt the

class, it's possible to teach them respect for others and the environment.

If a child is feeling restless, it's usually just a matter of going out

together into the hall, to the gym or for a drink of water."

Her best advice: "Listen as much as you can, even though there is

less and less time to do so." And take even more time to listen to

children with ADHD. Fecteau recalls a student who resisted holidays and

weekends. "We discovered that he really liked school because we listened

to him here."

Fecteau says she learns something every day with the children. "You

can imagine after a holiday everyone is more hyper, more agitated. We

have to listen more, calm them more."

One trick is deep breathing-take the child aside and take three deep breaths

together. "It calms both of us and they know it."

The teaching assistant credits her success to "great training-I had

good coaches in the teachers I worked with." She is currently taking

correspondence courses through Toronto's Collège Boréal

and expects to have her credentials for teaching assistant to children

in difficulty within two years. Three years after that she hopes to be

a teacher.

|

![]()