|

Teaching behind Barsby Gabrielle Barkany |

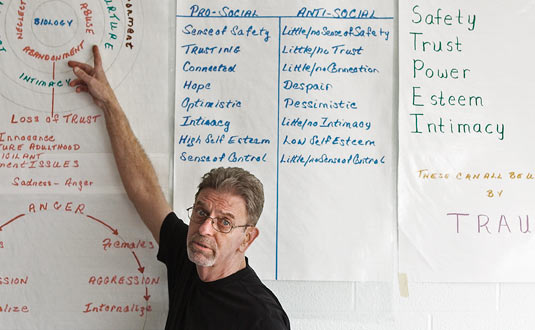

John Lynch has no ordinary students. In his classroom, all students have significant emotional and social problems stemming from serious trauma and/or ongoing neglect. Some have committed crimes. For the last 18 years Lynch has taught English, history and social sciences at Syl Apps, a secure treatment centre operated by Kinark Child and Family Services. He works here because he wants to help change his students’ lives. In some respects the high school at Syl Apps looks like any other: teenagers linger and fool around in the hallways, students ask questions in class, a girl offers her latest drawing to the teacher. But the series of locked doors to enter the school and V-shape at the top of the chain-link fence outside the window are reminders that this is a secure facility, and students’ mock salutes to staff as they enter classrooms have an added edge. Syl Apps has a capacity of 72 residents. But numbers shift and in May of this year about 50 young people were housed there – 20 in treatment, 30 in custody. Those in treatment generally stay for 12 to 18 months. Of those in custody in May, 14 had been convicted under the Criminal Youth Justice Act and were serving sentences ranging from three months to five years; the rest were in detention, staying on average five to ten days. All residents attend the on-site school, which is managed by the Halton DSB. There are 15 teachers here and they work with teams that include social workers, psychiatrists, psychologists, chaplains, clinicians and representatives of various cultural groups. The problems these kids face are complex and there are no quick fixes. PioneersTwelve years ago, Lynch and Richard Meen, the psychiatrist and clinical director at Kinark, developed the Pioneer Program to address both education and therapeutic goals for residents during their first months. The semester-long program is offered to females one semester and males the next. “Both the girls and the guys are dealing with a lot of trauma in their lives – neglect, abuse and abandonment,” says Lynch. But the outcomes are often different. “With the male population, we are addressing the cycle of aggression and violence, while the girls tend to be depressive or borderline personalities.” The program’s aim is to help them understand the inherited behaviour patterns, the emotional relationships and other psychological factors that inform their interactions. It is delivered in two 70-minute periods each day for credits within the curriculum context of English or senior social science. Not all students at Syl Apps take part in the Pioneer Program. They are selected by their resource group – a team of medical and social workers and teachers. “In order to benefit from this program,” explains Lynch, “they must be able to communicate in a group, and they must have some capacity for reflection and insight.” The program is voluntary. Students have to be open and ready to participate and it takes some time to build trust. These youths have often had poor track records in school, and the first requirement is an environment in which they feel safe. Teachers strive to create a structured environment that is also warm, open, tolerant and inviting. “For the first six weeks, we don’t get anywhere near their personal issues,” says Lynch. But the program takes away some of the fear of having to sit in front of a social worker, psychologist or psychiatrist and start spilling their guts. And things gradually change. “It helps students gain the mental health skills they need,” says Jane Powell, principal for Syl Apps and other section 23 facilities in the Halton DSB. “It prepares them to learn academically and it readies them for their work with a social worker, psychologist or psychiatrist at the centre.”

Whether they are high-risk offenders or not, explains Lynch, “These youth need to understand and come to terms with the experiences that have led them to be here.” Students look at the effects of major life events and chronic illnesses and disorders such as alcoholism and depression, as well as education and work. They learn to understand the social, cultural and environmental factors they grew up with and behaviours that they learned – and then to explore options. “It’s not to provide them with an excuse but to provide them with some degree of insight,” Lynch says. “They need to be able to express their needs as opposed to acting them out. The hope is that it will, over time, reduce their risk of re-offending.” From what students say, the approach works. “The more I learned about myself, the more open I was to school,” one student explains. “In the past, I didn’t know how much it would take to push me over the edge. Now I understand my limits and how much it takes before I’m going to get irritated and should walk away from a situation. If I didn’t have that, I would be at huge risk to re-offend.” Although the Pioneer Program is a one-semester course, usually started near the beginning of a student’s stay, sometimes students repeat the program or return briefly to work on a plan for their discharge program or to prepare for a transition elsewhere. Preparing for releaseThe offenders in youth detention facilities will be released back into the community once their sentences are served. Meen and Lynch believe that treatment combined with education may not be a panacea but is crucial for most students’ futures and perhaps particularly for rehabilitation of offenders. And while they know former students have pursued productive lives, they do not yet have hard data on the program’s effectiveness. Meen recently hired a researcher to build an evaluation tool. They both believe that the program has helped Steve, a fair-haired, sturdy young man who, when he was only 14 years old, killed a former friend. Steve has now been at Syl Apps for five years and has begun work on a BA in Christian studies. He wants to be a minister. “People underestimate how resilient youth are,” Meen says. “They’ve often had to deal with a lot of trauma and neglect. So they need a haven and a lot of care, time and support. It’s not a quick fix. But given the opportunity to grow, they can do very well.” Teaching in these situations is a reminder that teachers are not just delivering curriculum, they are modelling behaviour and influencing lives. “Before, I thought that if I showed my feelings and talked about them, people would think I was weak,” Steve explains. “But John talks about how he feels about different issues all the time and I don’t think of him as weak. He is actually the strongest person I know.” “The more humane the approach,” says Lynch, “the more humanitarian the benefit. Rather than just locking them up and throwing away the key, there is a definite benefit in what these students can gain – in their quality of life and in the possibility to reintegrate and become contributing members of society.” “If you can’t engage the students, you’re going to face failure right off the bat,” says Lynch. “To connect with them, you need to create a structure that’s going to be safe and secure – emotionally, physically and psychologically.”

Lynch, who was once physically attacked by a female student, admits that working with young offenders can be challenging. “The youth we are working with can be very aggressive and quite violent. You need to be aware and respectful of that all the time.” Nonetheless, he feels that he can have a significant impact on these students, and that’s one of the reasons he continues. “It’s intense but you can build much more of an attachment with your students and it can be more personally rewarding than in a larger school,” he says. The main thing Lynch has learned from working with these kids is: “You must always work to gain their trust and respect.” And he has found that the greater the problems they have had, the better they are at reading others. “They know when you are judging them,” he says. “And they will shut right down. You can’t afford to be judgmental.” Tough casesOne of Lynch’s students is a beautiful, tough-looking 17-year-old girl. Mary, a former crack addict, is about eight months pregnant and her handcuffs are being removed as she arrives at school after a visit to the doctor. She says her mother is in jail. The father of her baby is as well – for murder. Mary has been in and out of Syl Apps since she was 12 for various reasons, including breach of bail and probation. Her current stay began last October. “I’m used to it because I grew up in the system,” she says. “I’ve basically just lived my life in here and in group homes.” Mary says she has always struggled with anger and the Pioneer Program has given her tools to deal with it. “I have to breathe and calm down. If a person upsets me, I just have to respond in an appropriate way. I don’t always have to scream. Because a lot of times when you scream, people don’t really listen.”

Speaking of John Lynch, she says, “He has been there for me more than my parents have, more than anybody else. He’s very supportive, understanding and a wonderful teacher. A lot of the gains I have made in my life are because of this program, because of the books John has given me to read and the way he cares.” This girl has very big challenges ahead of her. She says she will want to take care of the baby girl and will need to prove to child-welfare officials that she can take care of the child and herself. For the next six months, she will live in a transitional housing facility that provides support for youth, as well as educational programming. Steve is waiting to see if he will be granted parole this year. He will either go to a halfway house or complete the final two years of his sentence in a federal penitentiary. But if he ends up in a federal facility, he might encounter some difficulties in continuing his postsecondary education. (See Teaching behind Bars, page 33.) For now, there is hope that this young offender may possibly have a productive life, due in part to the education and treatment he is receiving. “Even though some of these kids have done truly awful things,” says Powell, “it is important to remember that the reason they are here, with us, is that they are still children and they need our care.” Names of students in this article have been changed. Education in Care

|