Heather Gibson Elizabeth Hay recalls Ross McLean

|

|

|

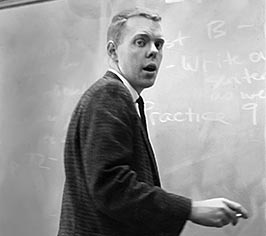

Ross McLean in 1967 |

McLean’s approach to teaching was just as unique. He urged students to look for knowledge and culture beyond the confines of the classroom. He pushed senior students to get involved in their own higher learning at nearby University of Guelph by visiting the campus library, attending film festivals, seeing drama productions and hearing guest speakers and musical groups. The goal was to make everyone aware of what was available on campus and give them an alternative to the standard night at home, watching television.

“He encouraged me to go to the university and sit in on some of the English classes,” says Hay. This experience, coupled with McLean’s knack for assigning homework that required plenty of research, strengthened her skills. “I certainly felt, in that year, that I began to learn how to write interesting essays.

“He created a very special atmosphere in the classroom that was incredibly conducive to learning. He didn’t need to dominate us or ignore us. He just had this steady, relaxed, even-handed approach that allowed all of us to be better than we’d ever been before.”

Hay unknowingly returned the favour. McLean credits her as the inspiration for something that’s helped many subsequent students. While proctoring one of her major term examinations – a two-hour history exam – he noticed close to an hour into it, while everyone else was writing furiously, that she hadn’t yet picked up her pen.

“Here I am monitoring a roomful of students, thinking, ‘My lord, what’s she doing?’ because I knew how much ability she had,” recalls McLean.

So when she started to write, he became curious. McLean knew the history teacher well, told him the story and asked to see the paper when he was done marking it. As it turned out, Hay had the top mark in the class – something like a 97.

What Hay had done in that first block of time, McLean later realized, was work through the various ideas in her head. “It was by far the most concise paper but also, frankly, the most brilliant, the most organized, the most tightly written.”

After seeing Hay in action, McLean conducted an experiment over the next few years. He’d ask his classes to resist the tendency to “write like hell” at the beginning of an exam. For 20 minutes he allowed them to use scrap paper to think their answers through, and only then were they given foolscap to begin.

“It drove some students nuts because it was opposite to the patterns they had evolved. In fact, I think a lot of them learned a lesson: the importance of doing some planning and organizing. And, as a result, all of them produced better quality work.”

Asked if he could foresee then the celebrated writer Hay would eventually become, McLean answers, “There was no question she had immense talent. I was well aware of that. And I was very curious about where that talent would take her.”

“He just had this steady, relaxed, even-handed approach that allowed all of us to be better than we’d ever been before.”

Where it took her was to a career in radio broadcasting followed by an unexpected turn to teaching. After 10 years at the CBC, Hay moved to New York City where she taught creative writing at New York University.

“I was living in the States with two small children. I had no connections to the radio industry there. I was writing but felt that I should try to earn some money. I had a friend who was doing some teaching at NYU – he gave them my name and that’s how I got the job.”

When Hay moved back to Canada, she continued teaching night school at the University of Ottawa until finally shifting to writing full-time in 1996.

Though this interim teaching career was seemingly happenstance, anyone who knows anything about Hay would think otherwise – teaching is in her blood. “School in all of its forms, has always been really interesting to me, partly because it consumes so much of my own life and also because of my father’s profession,” admits Hay.

Gordon Hay began as a history teacher, became a high school principal, was district president of OSSTF in the 50s and ended his career as a professor of education at Western’s Althouse College.

“I think his happiest years were in the classroom. He became a principal – with all of the headaches that involved – in an era when there was such a teachers’ shortage.”

Hay managed to stay out of her father’s classroom when he was a teacher but couldn’t avoid being one of his students when he was principal. For two years she walked the halls of Mitchell District High School with mixed emotions. “I felt a mixture of pride and anguish. Maybe anguish is too harsh a word but certainly sometimes, you know, worried on his behalf, embarrassed on his behalf, worried and embarrassed on my own behalf, but also proud.”

So it’s no coincidence that a few central characters in Hay’s Late Nights on Air happen to be teachers or have parents in education. And it’s no larger coincidence that Hay and former teacher McLean have kept in touch over the years. Hay sends her books to McLean and he reads them.

They finally met again six or seven years ago, over breakfast. Hay happened to be doing a reading near Guelph and decided she would try to tell McLean “something of what I felt about his excellence as a teacher.” Though she admits to being unsure of whether or not she did it properly.

“I think he was pleased and – perhaps just as I reacted when he said that there was nothing I couldn’t accomplish – somewhat disbelieving. He was never an effusive man, which is one of the reasons I was so comfortable with him. We didn’t dwell on it. I tried to tell him and then we moved on and talked about other things.”

No big surprise, the two ended up discussing writing, but this time things were different. “I do a little writing but not to any acclaim. I talked to her about some of the problems that I was having at that time and she gave me some advice,” says McLean.

And so student becomes teacher.

Perhaps it’s the willingness to learn from others that made him such a good teacher.

“Grade 13 was a happy year for me at high school. I began to come into my own. I had a sense – for the first time – of being capable, and that happened largely because of Ross McLean.”

Hay believes that “learning remains one of the most glorious things.”