|

Ensuring Literacy in an Age of ScrutinyAs Many as 25 Per Cent of High School Students At Risk of Not Graduating |

|

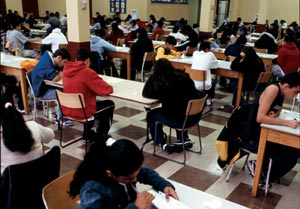

by Leanne Miller The final report of the province's At Risk working group rang the alarm in January 2003: Significant work must begin immediately or a large number of students will not graduate and will become disenfranchised young adults without hope for their futures. The facts were clear. In 2002 only 72 per cent of the Grade 10 students who wrote the Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test (OSSLT) for the first time passed it. Eighty-five per cent of students rewriting (having previously failed) in 2002 passed the test. Since success on the test is required for high school graduation, these results indicated that as many as one quarter of Ontario's high school students were at risk of not graduating. Such results did little to alleviate teachers' concerns about standardized testing. According to an Ontario College of Teachers/COMPAS survey in July 2003, 85 per cent of teachers believe standardized tests demoralize students, 90 per cent feel they do not improve learning and 88 per cent think they do not track student success. "Many kids who struggle with the OSSLT have superb hands-on learning skills but cannot do well, or actually panic, when they have to perform on demand - especially when taking a high-stakes test," notes Kerry Stewart, a literacy leader at Limestone District School Board and a member of the Ontario government's expert panels on numeracy and literacy. But arguments concerning what such tests actually measure or their efficacy aside, Stewart says, "When we saw that more than 60,000 kids might not graduate we knew we had to do something fast." Educators continue to seek solutions. Expert panels on literacy, numeracy and pathways (school-to-work initiatives) met throughout 2003 to develop recommendations for support of at-risk students. (The literacy panel's report was published at the end of October.) School boards have created at-risk leader positions to co-ordinate strategies and supports for these students. In the coming months their work will focus on the implementation of panel recommendations. The test-results statistics, available on the Education Quality and Accountability office web site (www.eqao.com), do help to identify particular problem areas. Eighty-five per cent of academic students were successful compared with 38 per cent of applied students. Seventy-five per cent of female students passed compared with 68 per cent of males. Devona Crowe, a former superintendent of education who has recently retired from the Thunder Bay Catholic District School Board offers one explanation: "Our system has been based on passive learning that has suited girls more than boys. And a focus on fiction engages girls more than boys. To engage boys we need more manuals and techie stuff." On the positive side, good literacy teaching helps to engage all students, not just those at risk. And across the province educators are moving to help their students succeed. Literacy Course an Alternative to TestThis September the ministry introduced a new Grade 12 literacy course, the Ontario Secondary School Literacy Course (OSSLC) in some schools and it will be offered at most schools during the upcoming semester. The reading and writing competencies required by the standardized test form the instructional and assessment core of the course. Grade 12 students who failed the test twice but complete this course successfully, earning a Grade 12 English credit, will meet the literacy requirement for graduation. Stewart explains: "As with many boards the most urgent priority at the Limestone board has been implementing the OSSLC. First we identified students who are currently in Grade 12 but did not pass. We made sure that they were signed up to write the test this fall if that was the best choice for them. These students all received tutoring to help them prepare. If the test wasn't the right route for a student - and for many it wasn't - we enrolled them in the OSSLC." As the school year began, the Limestone teachers assigned to teach the new literacy course learned strategies to teach reading and writing. They received planning time to develop handouts, course outlines, assessment materials and a similar introductory unit. Barbara Halliday teaches the OSSLC at Queen Elizabeth Collegiate and Vocational Institute in Kingston and Michelle Kehoe teaches it at Ernestown Secondary School in Odessa. The two English teachers were apprehensive at first. "I wondered who was mad at me," joked Halliday. "Now that I'm doing it I love it. It's the best course profile I've ever read." Kehoe says, "The kids have bought into the course. They know that it has been created just for them and they're motivated. It's their last chance and they know it." Expect Most if Not All Students Will PassHalliday explains how this course is different from traditional English literature. "There's no Shakespeare or novel study. We read high-interest short stories and we regularly read the newspaper. Sometimes the kids choose their own readings. They read things that are relevant and practical and this motivates most of them to read more than they ever have before." Kehoe explains other differences: "I have learned how to teach reading and I use strategies like previewing, chunking activities into small pieces and having the kids read backwards to find key vocabulary." Shalane Lowry's students at Napanee District Secondary School discuss the differences between this course and the anxieties of writing the test. "There's no way to study for the test," says one student. "It stresses me out too much. If I didn't finish something, everything was wrong and that wasn't fair." Another student adds, "I need to listen to music to make me relax and I wasn't allowed to. I started tapping my fingers on my desk when I got nervous and I was yelled at to be quiet. It was no good. Here, if I'm nervous I can listen to music or walk around a bit and it helps me concentrate." Lowry points out the difference between the test and the course when she says, "In this class, we are process-oriented; the OSSLT is product-oriented." Reaching HigherThe web site Reaching Higher is one of hundreds of literacy initiatives that have been developed in Ontario in the past three years to address these issues. Judith Taylor, Peel District School Board's literacy co-ordinator and a member of a multi-board team that worked on Reaching Higher, says that the resource package available on the site - a series of practical, ready-to-use documents - provides a starting point for a cross-curricular team of teachers. The resource was delivered to board leaders throughout Ontario. It was developed to offer teaching and learning strategies for students in Grades 6 to 9 who were performing at Level 1 and below in reading, writing and communications skills. The site states that "Literacy is the responsibility of all teachers in the school, and there are many opportunities to develop literacy skills in all subject areas." To help teachers meet that responsibility a professional-development video and viewing guide were created and the Ministry of Education has distributed one copy to each board leader for students at risk. University and Peer TutoringThe Limestone District School Board has taken advantage of its close relationship with Queen's University. For the past two years Faculty of Education students wanting to work with high school students (and undergraduate students applying to faculties of education) have been trained to work as paid literacy tutors within the local board. Tutors are hired in the fall to work in all secondary schools specifically to help at-risk students prepare for the OSSLT. The tutors return in May and June. They help to compile information concerning at-risk students - identifying their literacy strengths and weaknesses as well as strategies that will help them prepare for the test. Limestone also uses peer tutoring. Anne Marie McDonald, the literacy consultant for Grades 7 to 12, explains how peer tutoring works: "Senior students begin training in September. They learn reading and writing strategies similar to those used by elementary teachers. It's a rigorous and demanding assignment and these student tutors earn a credit for their work." Many are students who want to become teachers themselves. All Grade 9 students are tutored in the fall of each year and from these sessions schools can determine who needs more support. Practice TestsMany boards have Grade 10 students write practice literacy tests. Some begin earlier. This fall all Grade 8 students in Limestone district wrote a practice test designed to help determine how well students had acquired the skills expected by the end of Grade 7. Staff will use the results to assess strengths and weaknesses in their programming. They hope to find out how prepared students are for writing high-stakes tests and whether they are learning the literacy skills they will need to succeed. Changing TimetablesIn September 2001 principal André Labrie of La Salle Secondary School in Kingston piloted a new timetable. Instead of four 75-minute periods the school now has four 60-minute periods and time for one additional 60-minute multi-subject instructional period (MSIP). Students have their regular four classes each day plus a one-hour supervised study period. One teacher is assigned for every 30 students. Students in any one MSIP may be from all grades, with varied levels of ability. Their course selections determine their timetable and the MSIP comes when they are not in one of those classes.

Each MSIP begins with 20 minutes of silent literacy work - reading or writing. Reading choices can be subject-related or personal. Following that, students may work alone or in small groups. They may work on assignments, make up work they missed due to absences or get help in areas where they are falling behind. Students can also sign out of the classroom to work in other MSIP classes - a science or computer lab or the library. Michael Howe, a vice-principal at the school, explains: "There are multiple MSIP classrooms during each period of the day. I schedule them so that teaching staff in each of the core areas - English, math, social sciences and science - will be available during each time slot." "If kids need extra help in math they can go to one of the math teachers. But students could also go to the computer lab or take on extra projects in the woodworking shop." It is easy to see how the flexibility of MSIPs would be ideal for students who need extra help with their literacy skills. Some also take advantage of peer tutoring, which is primarily focused on literacy. Labrie points out that it's not a study hall. "Student learning is the single most important motivator for everything we do. We're developing the ability in our students to sit and work for one hour every day and we're giving them time during school to reinforce daily instruction." He says, "MSIPs are structured to facilitate consolidation, remediation and extensions of students' learning. The five-period day using the MSIP gives us a flexibility that is not available in any other timetable structure that I know of. This flexibility has resulted in a professional dialogue among staff that is focused on teaching and learning, specifically related to at-risk students." Labrie is extremely proud of two success indicators. "First," he reports, "our OSSLT test scores have improved dramatically. In 2001, 57 per cent of our students passed the OSSLT. In 2002, 86 per cent were successful. Second, La Salle has the board's highest percentage of students at the applied level who have passed the test. Our goal is to take care of 100 per cent of the students in our building and we're working hard to reach that goal." Such success is highly motivating. Teachers at La Salle have more student contacts and 15 more minutes in class each day than teachers in most semestered schools, but more than 90 per cent voted to continue the program. Literary Resource StrategistsIn York Region District School Board every 10 secondary schools have an extra teacher, called a literacy resource strategist. These resource people support their colleagues and provide professional development to help improve the literacy skills of Grade 9 and 10 students. They co-plan and co-teach with subject teachers, integrating literacy strategies into the curriculum. Cathy Costello, York's Curriculum Co-ordinator for Literacy, says, "The strategies complement and enhance what teachers are already doing with their students." Costello points to research showing that Grade 9 students are exposed to as many as 2,000 new words during the year and notes how something as low-tech as a word wall can help improve student learning. In a Grade 9 geography classroom, for example, a word wall may be used to list and define terms such as esker, tundra or tectonics. The word wall keeps correct spellings and definitions before their eyes so students have a ready reference and reinforcement of what they are learning. Costello observes, "It has always been said that in Grades 1 to 3 students learn to read, and from Grades 4 to 12 they read to learn. But that's simply not true - especially for at-risk students with weak literacy skills. We continue to teach them literacy strategies that will help them read, write and comprehend because that's what going to make them successful, both in school and beyond." Tailoring ProgrammingRita Mannella is the Chair of Languages at St. Ignatius High School in the Thunder Bay Catholic District School Board. "Literacy is not solely the responsibility of English teachers," she points out, "It's everyone's job." Last year, Grade 9 teachers in both applied and academic subject areas at St. Ignatius developed lesson plans with their colleagues so that literacy skills were integrated throughout and there was consistency in terms of language use and expectations. This collaboration gave students many cross-curricular opportunities to practise and use the literacy skills they need. By June, in all Grade 9 classes, teachers could identify which students were at risk and which things gave them the most trouble. From this data Mannella and her colleagues then developed their Grade 10 literacy programming. Manella developed a short guide for colleagues to use with the 96-page Grade 10 Test of Reading and Writing Workbook. The guide presents activities that relate to the five reading and writing components of the OSSLT, allowing teachers to address weaknesses that they identified in Grade 9. Time Will TellOSSLT results for 2003 will be released at the end of January and time will provide the measure of success for these varied strategies. But it is clear that Ontario's educators are committed to helping their students succeed with the new curriculum and the literacy test. The programs touched on here are definitely having a positive impact on student learning. And the dedication and innovation of educators make it a certainty that there will be fewer at-risk students in Ontario's schools. |