The Courage to Teach in Afghanistan

Though schools are open, death threats persist.

by Sally Armstrong

Transition to Teaching 2006: The best and worst of times

by Frank McIntyre and Brian Jamieson

Transition to Teaching 2006: Help for new teachers slow in coming

by Frank McIntyre and Brian Jamieson

Living the Standards

by Lois Browne

Vimy Revisited

Port Perry teacher Dave Robinson co-ordinates teachers and more than 3,600 students on this trip to the historic ridge.

by Leanne Miller

The Courage to Teach in AfghanistanThe main dilemma facing the teachers of Afghanistan has little to do with students and supplies or with issues such as salary, work hours and equipment.It is the fear of being beheaded for teaching children.by Sally ArmstrongPhotos by Lana Slezic (except where noted) |

It's not the 60 children per classroom that gets a teacher in Afghanistan down. It's not even the fact that there aren't enough chairs for the students or that teachers have to share blackboards and have few, if any, textbooks. The real dilemma facing the teachers of Afghanistan has little to do with students and supplies or with issues such as salary, work hours and equipment. Their plight is death threats that come in the form of letters from the Taliban dropped on their doorsteps while they sleep – letters that warn them to stay away from the schools, to stop teaching or face the consequences. And it's the news of teachers and principals being murdered – beheaded for teaching children to read and write – that gets the teachers in Afghanistan down.

With rare exceptions it doesn't stop them. Everyone knows that education is the way forward for a country that has been through 23 years of civil war and five years of the Taliban's brutal medieval theocracy, which closed all the schools in the country. But the stakes are high. While teachers may hold the key to change in Afghanistan, thugs like those in the Taliban want them dead.

Today, there are six million students back in the classrooms; two million of them are girls. No census has been done in Afghanistan, but the population is estimated to be between 22 and 25 million. Since the life expectancy in this troubled country is 40 years, one can deduce that the number of students still being denied an education is vast. Changing that fact depends on three things: security, budget and staffing.

When the Taliban was ousted in November 2001 and a new interim government was formed, Sima Samar, the Deputy Prime Minister at the time, said, “We cannot afford to wait for the schools to be rebuilt. If there's no school, sit the students under a tree. Start classes today.”

Breaking bread

The confounding fact was that the government didn't have enough money to pay the teachers. So while some schools opened, most remained closed. That's when a Canadian woman called Susan Bellan got involved in an experiment that has become a stunning success.

“I wanted to help but I didn't know how,” recalled Bellan when I spoke to her in her Toronto store, Timbuktu. “I decided that, if I could find a way to get money to pay the teachers, they could make a difference in the lives of Afghan girls who had been denied an education and, ultimately, in the recovery of the country.”

|

Today, there are six million students back in classrooms. Two million of them are girls. |

Bringing new meaning to the power of one, she invited a dozen friends to a potluck supper and, at the end of the evening, asked each one to write a cheque for $75. Her goal was to raise $750 – the salary for one teacher for one year in Afghanistan. The idea spread like a prairie fire across Canada and she named the initiative Breaking Bread for Women (www.breakingbreadforwomen.com). Today, more than 75,000 girls in Afghanistan are attending school because of the creative determination of this one Toronto woman to make a difference.

Shadows lifting

The schools that the Breaking Bread program supports are scattered all over Afghanistan. In the late fall of 2003 I visited a school in Jaghori, in the central highlands of Afghanistan, to find out whether the concept was working.

It was bone-chillingly cold and barely light when I arrived at the school at 7 AM. The area superintendent told me the kids walk for hours to get to school and some arrive well before the 8 AM start time.

As the shadows of dawn started to lift off the mountains the sight in the distance was remarkable. Students were coming over the hills, down the valleys, in twos, in fours, as far as the eye could see along the furrowed pathways and dusty byways. Like penguins, in their black school dresses and white head scarves, they came – little kids, teenagers – the blameless youngsters who had borne the brunt of the Taliban's ruthless decree that girls were forbidden to learn. Tucked in their little satchels and souls were the hopes and dreams of a generation.

“If there's no school, sit the students under a tree. Start classes today.”

The teachers in the 17-room school gathered at the door awaiting their students' arrival. The old man at the gate of the walled property pulled on the rope attached to an ancient iron disc perched at the top of the entrance – bong, bong, bong.

Back-to-school was never a more powerful milestone.

The 1,950 girls at this Shuhada School attend classes in shifts – half in the morning from 8:00 to 11:30 and the other half in the afternoon from 1:00 to 4:40. About 25 km away another 1,000 students do the same at Shuhada Bosaid School, also funded by the Breaking Bread initiative. The six- to 12-year-olds have never been to school before. The teenagers had their education halted by the Taliban when they were in primary school.

Class sizes range from 60 in the primary grades to 45 in the senior classes. The infectious enthusiasm is hard to miss in the classroom, where the students clap every time someone gets the right answer.

Both teachers and students are committed. “It's not enough to read and write,” says principal Habiba Yosufi. “My students will be able to go anywhere with their knowledge.” On behalf of the 35 teachers who work with her she says, “We couldn't do this without the money from the Canadian women.”

Promise and presidents

I'd become so accustomed to faces full of fear and furtive glances during the hateful Taliban period, I fully expected the children to avert their eyes as they walked past me into the school. Instead, they stopped where I stood on the doorstep, asked what I was doing there and, with the solemn earnestness that makes children so appealing, they shared their dreams with me right there on the threshold of the school that they saw as their pathway to the future.

|

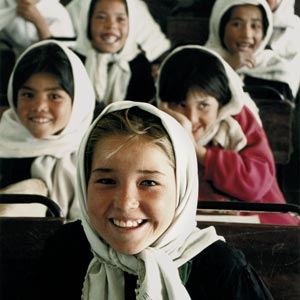

“I will learn. And then I want to be an astronaut.” The enthusiasm of 10-year-old Wahida (foreground) and her classmates is hard to miss. Photo: S. Armstrong |

With her green eyes dancing and her blond hair peeking out from the head scarf that had gone askew, 10-year-old Wahida (like many Afghans she has no family name) said, “I will learn. And then I want to be an astronaut.” This from a girl who was forbidden to leave her home for five years during Taliban rule – a girl who knew little of the outside world before September 2001 when the outside world came to her via bombs and promises to rid her people of the terrorists who had trespassed on their lives.

Sixteen-year-old Fatima Anwary, a dark-haired, brown-eyed beauty in Grade 12 said, “I'm going to change Afghanistan. I'll do it by getting an education. Knowledge makes change.” And little six-year-old Parwana piped up, “This is my school. When I'm a grown-up I'm going to be somebody.”

“Who is that somebody?” I asked.

“The president of Afghanistan,” she replied matter-of-factly.

Securing a future

On a recent visit to Afghanistan I checked in at the schools again and once more, this time in Kabul, I found classrooms of children with plans to be somebodies. But the same confounding problems are getting in the way. The biggest, as the teachers can attest, is security. Although the Taliban insurgency is focused on the four southern provinces, it's creating a backdrop of fear for the whole country. “Without security nothing else works – not the schools, not the judiciary, certainly not the well being of the citizens of Afghanistan,” says Samar, now Director of the Independent Human Rights Commission of Afghanistan,

The Canadian soldiers serving in the Kandahar district, the most dangerous assignment in the whole country, are witnesses to her corollary.

Canadian Brigadier General David Fraser, NATO Commander for the southern provinces, says security in the region is what's needed for schools to stay open and teachers to do their jobs safely. “We're here to build, to facilitate, to give this country back to the Afghan people. I spend most of my time talking to elders, soldiers, police officers and asking how we can help.”

“We couldn't do this without the money from the Canadian women.”

The fire-bombed schools, the terrified villagers, the absence of girls and women in public places and the night letters with their death threats to teachers are among the issues soldiers encounter on their daily patrols.

Even before that security has been established, Samar says, “We need to focus on teacher training.” A visit to any classroom in Afghanistan makes this need obvious. Most instructors are those who finished high school rather than professionals who have trained as teachers. Rote learning is still the method of choice. The teacher points to a letter on the blackboard and 60 students shout out the reply – over and over again. Issues such as learning disabilities, concepts like age-appropriate curriculum and standardized testing are unheard of.

Seeing the world

But in the classrooms today, the students defy the odds. They've barely learned to read and write and are already saying, “It's the time of technology. We want computers. We want to be part of the world and get on the Internet.”

That attitude has spilled over to adult learners as well, who are attending literacy classes in droves. With an illiteracy rate of 85 per cent, learning to read and write has become the new panacea for Afghans, who invariably refer to their illiteracy as being blind. When asked to explain the connection one woman replied matter-of-factly, “I couldn't read, so I couldn't see what was going on.”

|

Rote learning may still be the principal method of instruction, but student enthusiasm is everywhere. |

In fewer than a dozen words she describes the underlying reason that political thugs deny education – so that people haven't the knowledge that would threaten their power.

While the troubles in Afghanistan are still immense, there are signs that education is about to become a priority. Chris Alexander, Deputy Special Representative for the United Nations, feels the appointment of Haneef Atmar as Minister of Education means that teachers, students and schools will get the attention they badly need.

“The threat of orthodox Islamic conservatives with a reductionist view of their religion taking power will fan the flames,” says Alexander. “But there's a much larger community that rejects that. Ordinary people here want to embrace education and women's place in society and Afghans' place in the world. With Atmar as minister there will be progress. Watch this space.”

It won't be the first time teachers are struck with the responsibility of altering the course of a country and the fate of its citizens.

The words of Aristotle come to mind: “The roots of education are bitter but the fruit is sweet.”

Breaking Bread for Women

The Breaking Bread for Women web site tells you how to organize an event to raise money for teachers in Afghanistan and how to get tax receipts.

It includes comments about various events across the country and gives details about the teachers and students this initiative has supported.

For more information visit www.breakingbreadforwomen.com.

Other aid and education organizations working in Afghanistan

UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund)

- mandated by the UN general assembly to advocate for children's rights, meet their basic needs and expand their opportunities

- in Afghanistan, focuses on emergency preparedness, response to natural disasters, health and the demobilization and reintegration of child soldiers, as well as education

Two million children of primary-school age do not attend school. The gender gap in education is narrowing, but girls still lag far behind boys in school enrolment. UNICEF and its partners have trained 30,000 teachers and supplied educational materials for 4.87 million students. In areas with no schoolhouses, tents, teacher training and learning materials have been provided to offer informal learning opportunities for 250,000 children. More than 500,000 girls enrolled in school for the first time in 2005.

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization)

- in Afghanistan, supports teacher training, the rebuilding of schools, literacy programs, and information and communication technologies in schools

Afghanistan suffers one of the world's lowest literacy rates. An estimated 48 per cent of Afghan men and 78 per cent of Afghan women over the age of 15 cannot read or write. The Literacy and Non-formal Education Development in Afghanistan project (LAND AFGHAN) is focusing on building up a nationwide network of literacy teachers trained in modern non-formal education methods and has been working with Afghan educators to develop a national literacy curriculum framework.