As an actor, writer and producer for several decades, Paul Gross has become a Canadian entertainment icon.

But as much as the name Paul Gross is synonymous with Canada and the country's best in film, television and theatre, it was a bit of a journey before he could finally call Canada home. Born in Calgary, Gross grew up in a military family. The Gross clan moved to England, left for Germany, returned to Canada, went to the United States, and then came back to Gross's home and native land.

It's important for any student to connect with that one special teacher. According to Gross, that bond is even more vital when you're a kid who has been forced to move around a lot.

"Generally speaking, I think all kids in school need to find that one teacher who galvanizes them," Gross says. "It seems to be as simple as the teacher who fires you up. And some kids, I think sadly, don't find that."

Gross was one of the lucky ones. He found a teacher to fuel his fire, and his name was Tim Jecko.

Gross is well-known for the TV shows Due South, Slings and Arrows and Eastwick, the films Men with Brooms and Passchendaele, and a long list of acclaimed theatre roles. He has many credits both in front of and behind the camera but admits that, if he were forced to choose, he'd probably describe himself as a writer.

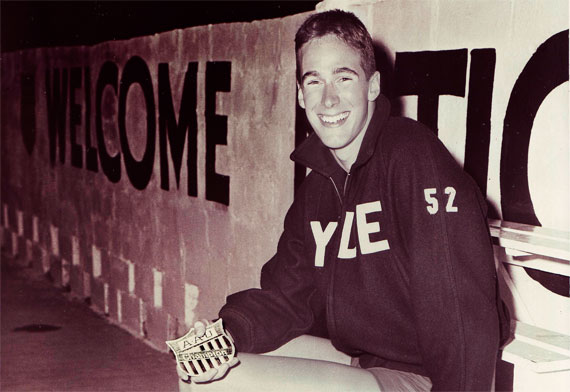

Jecko - who died in 2005 at 66 of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig's disease - was fairly famous himself, first coming to prominence as an Olympic swimmer. He was part of the US Olympic team that competed at the 1956 Summer Games in Melbourne, Australia. Jecko may not have won a medal, but the acclaimed student-athlete subsequently held world, US and NCAA swimming records.

Tim Jecko at the 1957 Amateur Athletic Union Championships

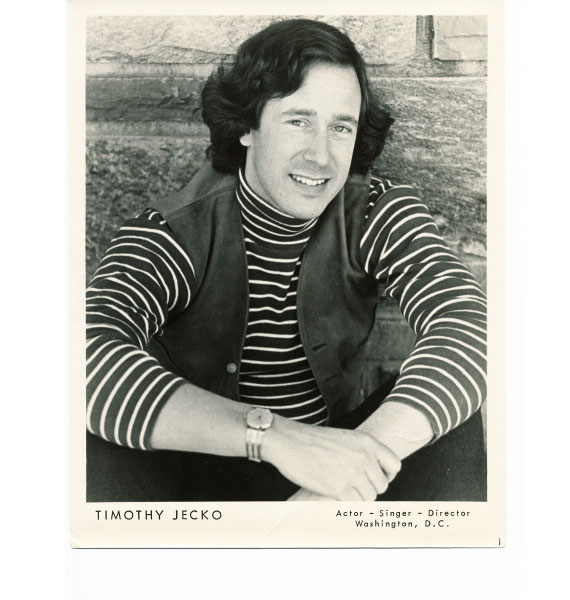

Then, after teaching high school drama for some time - which is how he crossed paths with the young Gross - Jecko became a professional actor of some repute, appearing in countless stage productions and doing episodic work on TV.

"I'm not even really sure how he came to teaching," Gross says.

Actually, Jecko was a Yale University drama school graduate and always had the arts in his blood.

"When I met him, he was at a high school called Yorktown, and that was in Arlington, Virginia," Gross says. "Overall it was a terrific school, and he was a fantastic teacher."

Prior to meeting Jecko, Gross says, his status as a good or bad student was usually related to the particular school he was attending. "It really depended on the school. Every school can be good for some of the students, but not every school can be good for all of the students. I think it depends on how that match works.

"I was lucky, I went to a couple of really good schools. Now, there were a couple that were not so good, too. But I had a natural capacity for academics, so I never really had to work at it that hard.

"I had a great memory, which is largely what the academics are about in high school. You know, 'Tell us about the War of 1812.' You might as well be copying it out of a book. It was just regurgitation."

In Gross's mind, the school at which he met Jecko was one of the best he encountered.

"That school was quite extraordinary because I had three or four teachers who were really inspirational," Gross recalls.

"As time goes on, I think most people develop a certain degree of respect for the job teachers have to do. I think it's fantastically difficult. And it's way more complicated now."

So what was it about Tim Jecko that clicked with Paul Gross?

He gave us a lot of room to move, and he was extraordinarily talented.

"He gave us a lot of room to move, and he was extraordinarily talented," Gross says. "So we did shows like The Canterbury Tales and Doctor Faustus, just bizarre kinds of choices.

"Looking back on it, sometimes I think, 'Who would throw a bunch of kids in their second year of high school into Doctor Faustus?' It's kind of extraordinary when you think about it. That's hugely ambitious. Not too many people put that thing on. I don't even know if Stratford has ever done it, for instance.

"So he was pretty bold. And yet at the same time, he found a way of providing us with the stepping stones to enter that kind of realm. He would give us assignments like, 'Think of your favourite movie scene and write down the dialogue and do it.' And so we would go in and do these scenes. And I remember doing Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid - on the cliffs before they jump."

Gross believes that Jecko's enthusiasm, sense of humour and youth all contributed to his effectiveness. Jecko came across as more of a peer than a great sage dispensing wisdom.

"It's kind of hard to tell what that alchemy is, where some teachers click with certain kids, and other kids don't find them inspiring at all. I don't really know how that works.

"But Jecko's commitment was formidable. He spent a lot of hours outside of school, hours that in the strict sense were not part of his job. My recollection is that pretty much everyone who worked with him loved him."

According to Gross, commitment and patience are the qualities that serve teachers best, although he stresses that he is not an expert on the subject.

"I would be very nervous about giving teachers advice," he says with a laugh. "I'm not a very good teacher, actually. When I've been called upon to do that, I'm kind of impatient.

"But when I've observed people who are good at it, it seems they have an ability to dismiss their own egos and serve their pupils. When I think about the teachers I had who I thought were fantastic, that was probably the quality they had. "I imagine it also takes a while for teachers to get used to teenagers' apparent air of indifference. Some of them are quite engaged, but God forbid they should show that."

Gross says he did not stay in close touch with Jecko in the years leading up to his death in 2005. But back in the 1990s, Jecko got in touch with Gross through the production offices of Due South, and the pair had a reunion of sorts in Toronto.

"He was up for some conference because he also made part of his living telling CEOs how to give board speeches and that kind of thing. He was sort of a coach; it was one of his sidelines. We had a great time. We went and had dinner, and it was fantastic.

"Yeah, he was aware of how I felt about him. I said it a couple of times in interviews in the States when I was on Due South. And yes, he said it was very nice for him to hear that I thought he had some influence on me.

"I'm not sure where I would have ended up otherwise.

"In Grades 6, 7, 8, I was drawn toward the theatrical stuff. But I wasn't really thinking about it in any kind of coherent way, along the lines of, 'Yes, I'm going to grow up and do this.' So it wasn't until Tim that it was given a shape, that I actually saw it as something I could apply myself to and learn some craft and actually do that for a living.

"Really, I owe that to him."