What happens when learning takes place at a distance? As online courses multiply in Ontario, teachers explore how they can help students succeed.

by Stuart Foxman

"I have a sense of who my students are. I care about them, and I feel that bonds have been formed." Those words aren't surprising coming from a teacher, in this case Rebecca Lupton, OCT, about her Grade 12 creative writing students. Yet Lupton wouldn't recognize her students if she saw them on the street. She has never even been in the same room with them.

Lupton is an e-learning instructor working out of Loyalist Collegiate and Vocational Institute in Kingston, and her class includes 25 students from across Ontario. They log in at different times of the day to complete assignments, upload their work, post on discussion forums and e-mail their teacher.

Teaching is about making connections - getting to know students, providing them with support and engaging them in the subject matter. So when you are separated from your students by space and time, what are the consequences? How do you relate to them? How do you ensure their comprehension? How do you know which of them are struggling so you can come to their assistance?

There are many critical questions surrounding e-learning, but for Lupton all teaching starts with one overall goal. Instead of standing in the classroom Lupton may be sitting in an office with her laptop, but the objective is the same: "helping students succeed."

That's also how the Ministry of Education describes online courses. "Ontario's e-learning strategy provides students with more choices to learn and succeed, regardless of their location, learning style or circumstances," says Gary Wheeler, spokesperson for the Ministry.

The Ministry says that e-learning supports student achievement by serving learners whose needs may be beyond what can be met in a regular classroom, including those who:

- are on individualized education plans

- attend small and rural schools with teachers who have fewer specialty qualifications

- attend schools with lower enrolments

- have timetable conflicts

- are elite athletes

- are at risk.

Ontario's e-learning strategy provides students with more choices to learn and succeed.

The traditional classroom, with direct teacher-student interaction, is the ideal, says Perry Cavarzan, OCT, a District E-Learning Co-ordinator for the Ministry of Education and Secondary Program Co-ordinator at the Simcoe Muskoka Catholic DSB. Yet, he finds, online courses can round out choices for students when a live class is simply not feasible or suitable.

Carolyn MacNeil-Verbakel, OCT, points to her group of 22 students who get credits for both online classes and co-op work. MacNeil-Verbakel, who works in Specialized Co-operative Education with the Thames Valley DSB, says that e-learning was the only way to re-engage some students who had dropped out.

Her own students and Lupton's may have different reasons for learning online, but in either case, says MacNeil-Verbakel, "it's about the students' well-being."

Participation on the rise

How widespread is e-learning?

A 2009 report by the International Association of K-12 Online Learning noted that 10 years ago about 25,000 K-12 students were enrolled in online courses throughout Canada. Today, there are about that many e-learners just in Ontario, according to Alison Slack, OCT, Co-ordinator of the Ontario eLearning Consortium.

The consortium is a network of 20 school boards that share e-learning knowledge, resources and students. Slack says that, among them, enrolment in e-learning courses jumped more than 50 per cent from 2008 to 2009 - and she expects that a similar increase occurred this school year.

Cavarzan wrote the first e-learning course offered by his board 10 years ago (it now uses courses provided by e-Learning Ontario) and acknowledges that there was apprehension back then about how students and teachers would respond.

As e-learning has developed, teachers perceive several advantages:

- more flexible scheduling

- improved matching of courses and learning materials to students' interests and knowledge level

- more variations and adaptations in course design to facilitate learning.

E-learning teacher Rebecca Lupton has taught a range of subjects - from creative writing to fashion design - out of Loyalist Collegiate and Vocational Institute in Kingston.

Moreover, says Semedo, e-learning can help northern boards like his to significantly broaden their offerings.

"Urban boards have the student population to support all sorts of courses, not just in e-learning but in classrooms," says Semedo. "We can't offer specialty courses, for instance, because we just don't have the students. But e-learning opens everything up. We're part of the Northeast E-Learning Consortium, and by pooling students from our district and region, we can hopefully have the critical mass that will allow us to run new programs."

Beyond benefits like that, e-learning advocates say that taking and completing online courses can encourage students to take responsibility for their learning and build self-confidence.

There are disadvantages, too. It can be hard for some students to adjust to the absence of a traditional course structure and school routine. If unmotivated or undisciplined, learners could fall behind. And students may feel isolated and miss direct social interaction.

It can also be difficult to simulate some courses online, notes Dominic Tremblay, OCT, an e-learning curriculum consultant whose clients include the Ministry of Education and the Centre franco-ontarien de ressources pédagogiques. He points to the virtual lab, where students click on beakers and thermometers in attempts to perform an experiment. "There isn't any satisfactory way of reproducing what the student can do in the lab," he says.

Clearly, e-learning teachers have to be well versed in online tools, but this type of teaching isn't solely about technology, says Tremblay. Whether delivered in a classroom or via an online learning module, a lecture can be equally compelling - or dreary. Tremblay says that it's up to the teacher, whatever the form of course delivery, to ensure that "students become involved in their learning."

In e-learning, as in the classroom, the teacher is still at the centre. Practising teachers write the courses, and the individual delivering any e-learning course offered through an Ontario school board must be a qualified Ontario teacher. That's the way it should be, states Slack. "The delivery method is different, but teaching is teaching."

She adds that in school settings, where supervision is required for e-learning, on-site teachers also help to ensure that learners are engaged.

Qualities that define best teaching

E-learning may make distinct teaching demands in terms of the schedule and the way of tracking student progress and providing needed help. But the qualities that define the best teachers are the same, says Rob Switzer, OCT, District E-Learning Co-ordinator for the Limestone DSB.

"Being flexible, accommodating different learning styles, providing feedback in a timely fashion and setting students up to be successful - that's what good teachers do in a classroom and what good teachers do online," says Switzer.

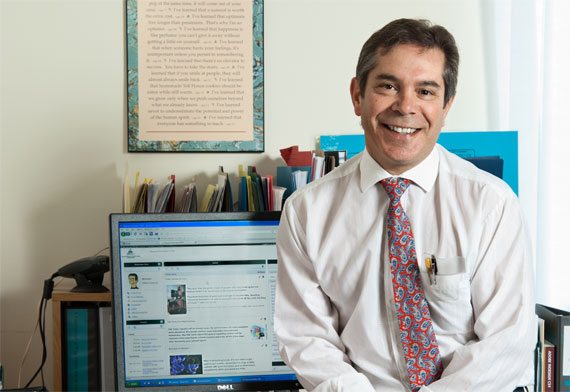

Perry Cavarzan, a District E-Learning Co-ordinator for the Ministry of Education and Secondary Program Co-ordinator at the Simcoe Muskoka Catholic DSB, says online offerings can broaden course choices for students who wouldn't otherwise have access.

E-learning teachers start with material developed by the Ministry of Education - just like classroom teachers - and still have the flexibility to modify content and the responsibility to motivate students, says Kirsten Elvestad, OCT, Student Success Administrator at DSB Ontario North East.

"You're not just a marker, you're still a teacher," says Elvestad, whose board offers 19 e-learning options. "Your job is to keep your students engaged."

Slack, who taught high school for 25 years and spent two years with the Ontario Ministry of Education helping to launch its e-learning strategy, agrees that the teacher-student relationship is the focus. "These courses are taught by a teacher who is online with them and available.

The student who sits at the back of the class and doesn't say anything - that doesn't happen in e-learning.

"A lot of e-learning teachers say that they know their online students even better than students in the classroom," says Slack. "The student who sits at the back of the class and doesn't say anything - that doesn't happen in e-learning. There are discussions all the way through."

The feedback Lupton offers is intensive. She feels it is more than what she gives in a traditional class. The nature of an online course not only encourages students to participate, she says, it lets them feel highly comfortable doing so.

Lupton knows that "there's no replacement for face-to-face contact." E-learning is not for everyone, nor will it (or should it) be a routine alternative to the live classroom.

Yet, students can still feel plugged in to their learning via online courses, says MacNeil-Verbakel. What's gratifying, she adds, is that "first and foremost, it's about the teacher's connection with the student.

"And students still feel that connection."