Lawrence Hill’s Remarkable Teachers

Mrs. Rowe, Margaret Shinozaki and Donald Gutteridge

by Brian Jamieson

To gaze into another person’s face is to do two

things: to recognize their humanity, and to assert your own.

The Book of Negroes

Imagine…

You’re a child living on a family farm. Every morning you wake to the aroma of freshly baked doughnuts. You rush downstairs and then…

Imagine…

Being torn from your family, sold into slavery and vowing to return, back across the violent ocean layered with the souls of your dead homelanders.

Imagine…

Living in another place or another time… being a man if you’re a woman or a woman if you’re a man… being 40 years older or living as a toddler.

Lawrence Hill lives to imagine and imagines for a living. But he can “100 per cent, absolutely” track his own success as a prize-winning, chart-topping Canadian novelist to the imagination and encouragement of teachers.

The Newmarket-born author rhapsodizes with memories of Mrs. Rowe, Margaret Shinozaki, OCT, and Donald Gutteridge, OCT, the way others gush about Hill’s novels. His most recent, The Book of Negroes, has been comfortably nestled among the top 10 sellers in Canadian fiction over the past two years and netted Hill the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and a visit with the Queen.

Hill, 53, cannot remember what Mrs. Rowe looked like. It’s the sound of her voice that lingers, and the kindness within.

The Grade 1 teacher at North York’s Mallow Road PS began every day the same way. She told the story of a young farm family whose kids would rise each morning to the smell of freshly baked doughnuts. They’d rush down the stairs to the scent and …

“Then the story would depart along some unpredictable path,” Hill says.

The description made him salivate. Beyond that, he was “intoxicated” by the mystery of not knowing what would happen next.

“It would have been the worst punishment imaginable to not go to school because I would’ve missed Mrs. Rowe’s story,” Hill says.

“Children love repetition,” he says. “They love it when they hear the same thing over and over and can predict exactly what’s going to be said to them. They also love to be shocked and surprised. She did a bit of both. She hooked us with the predictability of it in an intoxicating way. Then she’d really get us because we wouldn’t know where things would go.”

He retells the Mrs. Rowe story during his public readings, not as an example of a spark to his own writing, but as an acknowledgement of the importance of teaching.

“It happened 46 years ago, but I still remember it as if it were yesterday. That’s the influence she had on me.”

Teachers can have an incredibly profound and positive influence, he says. “They can leave a mark that lifts you for life. I’m sure that most people who are doing well in this world, who had the fortune of a good education, can think of at least one teacher who knocked them out and got them excited about learning.”

Hill lost touch with Mrs. Rowe. Never once, however, has he lost the feeling of respect she kindled. It’s a theme that courses through his work.

“You remember if you’re respected or not. And respect cuts both ways. If you feel you’re getting it, you’re likely to give some.

“Children know it at six; they feel it in their bones. Is this a good person? Is this someone I can trust? Or is this person someone to watch out for who has danger attached to them.

“Children have innate radar for danger. They’re not always right, but most of the time they are.”

Hill believes that children relax when they feel safe and respected, and when they’re relaxed, they’re apt to learn better. Or more.

“I write better when I’m relaxed. I certainly exercise or do sports better when I’m relaxed. And I certainly read better and learn better and engage in learning more when I’m relaxed. You need to relax to truly draw something in and engage with it. If you’re really uptight, it can be a barrier to learning.”

Rowe put him in a place of safety, and nothing felt more natural than learning.

When he was very young, however, a teacher – not Mrs. Rowe – told Hill’s parents he was developmentally challenged, would never do well in school and that they should never expect him to do more than scrape by. They never believed it, and they never let him hear those comments until many years later.

“Sometimes the things you don’t do are important, just like the things you leave out can make a novel better,” he says. “Oddly enough, the things you don’t say to your kids sometimes are some of the best parenting decisions you can make.”

Worldly engagement

It opened up a world of awareness, and I never left that state of awareness once Shinozaki brought me there.

It was Margaret Shinozaki, Hill’s Grade 2/3 teacher at Cassandra PS in North York, who spurred the writer’s awareness of the world around him.

Shinozaki says she did a lot of project work with her students. If there was an election, for example, she would divide the students into parties, encourage them to do research, involve them in debates.

“She was fantastic,” Hill says. “She had us assume positions as members of either the government or the opposition, and we had to announce our platforms and say, ‘My name is so-and-so and I’m a Liberal minister of finance and this is what I stand for.’ ”

Shinozaki had a heightened interest in human rights, having been subjected to the War Measures Act as a Japanese-Canadian. She invited guest speakers into the class, including Daniel Hill, Larry’s father, the first director of Ontario’s Human Rights Commission, founder of the Ontario Black History Society, and later, provincial ombudsman.

“She got us totally engaged with the politics and policy issues of the day,” Lawrence Hill says. “We rose to the occasion completely. It was very exciting. I loved it.”

Shinozaki remembers Hill as a “very creative and original thinker, even at that age. Larry was always aware of what was going on. He always asked thoughtful questions.”

Not surprisingly, he gravitated to journalism, his first full-time job after university, having earned a degree in economics from UBC and Laval and an MA in writing from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“It opened up a world of awareness, and I never left that state of awareness once Shinozaki brought me there. I remained interested in public issues after that.”

Open encouragement

Donald Gutteridge, Hill’s English teacher in Grade 12/13 at UTS, an independent school attached to the University of Toronto, further encouraged the future scribe.

Hill says he loved reading and writing and was “not a very good, but an active athlete” in high school. He ran track and cross-country competitively and achieved academically. “Not a genius, but I got into UTS, which was not easy, and did well.” He served as school captain in his last year (equivalent to school council president) and class captain the year before that. “I wasn’t one of those kids who aced every single thing.”

Gutteridge was “an instrumental influence” in Hill’s development. He allowed him to write short stories about issues rather than essays.

Does Hill recall any of the stories? “Yes I do and … they were awful.”

That was part of Gutteridge’s gift. The stories were not impressive, Hill recalls. No hint of future potential. No sign of a future Commonwealth Writers’ Prize winner. “I don’t think, if I were a teacher, that I would have been blown away by my great literary talent. It’s important to realize how long the incubation period is for a writer, particularly of fiction.”

Gutteridge isn’t sure what, if anything, he did that was special for Hill. “Kids would sometimes ask, ‘If I write something that you haven’t asked me to write, would you have time to look at it?’ My response was always, ‘Yes. Write as much as you like or as much as you have time to, and if you want, I’ll read it and make suggestions or we’ll have some kind of a dialogue about it.’”

He recalls as “promising” the first piece of fiction Hill brought him.

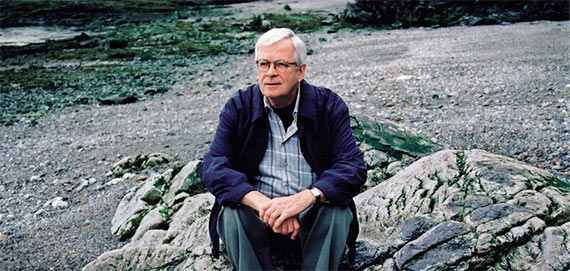

Donald Gutteridge – pictured here in 2002 at La Malbaie on the St. Lawrence River – was “an instrumental influence” in Hill’s development.

Years later, after reading Hill’s second novel, Gutteridge wrote his former student to say how impressed he was, that it was a significant piece of work, and that he was delighted that it had been so well received. They exchanged letters and in December 2000 had lunch. Later, they ran into each other in London, England, when Hill went to meet the Queen.

Gutteridge himself has a novelist’s eye for detail and a mind for recollection.

“Larry ran daily – for pleasure and to have a disciplined body to go with a disciplined mind.”

Everything he did, he did running, Gutteridge says. “He always had too much planned to get done in a given day, so he’d barely finish one thing before he had to be at something else.”

He says that Hill was thoughtful, taking others’ feelings into account and mulling everything over before speaking or acting.

“It was an odd combination,” Gutteridge recalls. “Always whizzing by and yet chewing over elements of his life or the next question he was going to ask. He was always very demanding on himself. One never knew how much.”

In class, Hill was “extremely attentive. He remembered everything he heard but was also sort of tense, as if there were an awful lot to digest.” The program was accelerated and sophisticatedly presented, Gutteridge says.

“I saw him as a young man with a bit of a mission, which would be borne out by some of what he’s written,” Gutteridge says.

Writing is a solitary pursuit. Boys, especially, tend to worry about letting the world know they’re engaged in it, Gutteridge says. He says he was always trying to figure out how to bring out the best in kids and make their inhibitions less important so they felt okay about what they were doing.

“Larry’s a terrific observer. He was recording all the time, and I think that’s a big part of the success of his work. He fairly consciously is always watching or listening for something to feed his own thinking and to broaden himself.”

Hill was active, confident, driven, amazingly aggressive – but in a polite way.

“If something really bothered him, he would be in your face, but with great courtesy,” Gutteridge says. “I knew him primarily as a pretty vulnerable 17-year-old, putting himself in positions where that vulnerability could be attacked, and he was always strong.”

Hill remains thankful for Gutteridge’s encouragement. He says it takes a long time and a lot of revision to allow most novelists to rise to their level of ability.

“You’ve got to find a way to encourage kids while they’re still writing things that, frankly, aren’t that good,” says Hill. “You have to believe they can move forward. Realizing I wrote probably not that well, it’s humbling and touching to think how encouraged I was.

“It’s not really teaching if you point out every mistake. It’s emotional torture and it gets away from that position of relaxation.

“If you’re a respectful, encouraging, positive presence in a child’s life, that child’s going to carry a piece of you in his heart the rest of his life. It’s got to be one of the most vitally important and grossly undervalued and underestimated careers in Canadian society to be a teacher,” says Hill. “The possibilities for doing good to somebody are just phenomenal.”

Imagine.