Lawrence Hill’s Remarkable Teachers

Mrs. Rowe, Margaret Shinozaki and Donald Gutteridge

by Brian Jamieson

Kurt Browning made a career skating through tense situations. But initially there was no skating around the intense gaze of his super-strict Grade 5 teacher, Leonard McLean.

Recalling those bygone school days in tough and tiny Caroline, Alberta, Browning – a former world figure skating champion and current host of CBC’s Battle of the Blades – says, “It was Leonard McLean’s first teaching job, and he was the heavy.

“He came in and he obviously had a swagger. He was the new sheriff in town, and he was going to teach these kids something. And he was not above throwing some chalk or an eraser brush at you if you were messing around or not paying attention.”

But something odd happened during McLean’s first year at Caroline School. First of all, the tough farm kids kind of bonded with the tough teacher.

“We took pride in the fact that our homeroom teacher was the toughest teacher in the school,” Browning says. “We liked it.”

And with that link established, McLean became more comfortable with the kids. And the kids became more comfortable with him.

Lo and behold, McLean is still in Caroline today. Retired from teaching, mind you, but still there, a pillar of the community.

“I think we changed him as much as he changed us, and I’m not putting words in his mouth – I’m only saying that because it was something he told us later,” recalls Browning, 44.

“He has told us, ‘I feel that you guys sort of helped me come to peace with my teaching style.’ And he went from being only the strict disciplinarian, with a cold shell, to someone who everyone looked to.

“It was a tough farming town, with tough farming kids, so we connected with his toughness. But he became so much more. Lenny became the guy everyone trusted. That’s what he was called, Lenny.”

Childhood memories of teachers often get tinted with new perspective as students grow into adults. At some point a light bulb appeared over Browning’s head, and he’s anxious to run something past McLean.

“I would really be curious to know something from him,” Browning says. “He came in with all this knowledge, and as an adult looking back, now I’m thinking that maybe he didn’t want to be in a small town. I don’t know. But maybe he didn’t want to be there.

“Perhaps he got there, and after a while he just sort of went, ‘This is cool.’ I’m just guessing, shooting in the dark at flies we can’t see. But even as little grade fivers, we could see that something changed for him within that first year.”

As Browning’s theory is relayed, McLean chuckles. “Wow – Kurt reads me well,” he says.

“Anything to do with Kurt Browning is always a pleasure. I guess I made an impact on him, but I wasn’t really thinking along those lines at the time. I was more surviving.”

It sounds as if McLean did far more than that.

McLean grew up in Montréal and got his teaching certificate in Edmonton. So after spending his entire life to that point in some of Canada’s biggest cities, he got his first teaching job in wee Caroline.

“I remember I called up my mom and said, ‘I got a teaching job in Caroline, but it’s not on the map,’ ” he recalls. “So Kurt read me right.

“At the time I said to my wife, ‘Well, we’ll stay here for a couple of years.’ That was our plan. But we were so close to the mountains, and I love the mountains. Within a year or two I just fell in love with the place. And my wife was accepted into the community quite easily, so what the heck, we looked at each other and said, ‘We can’t get any better than this.’

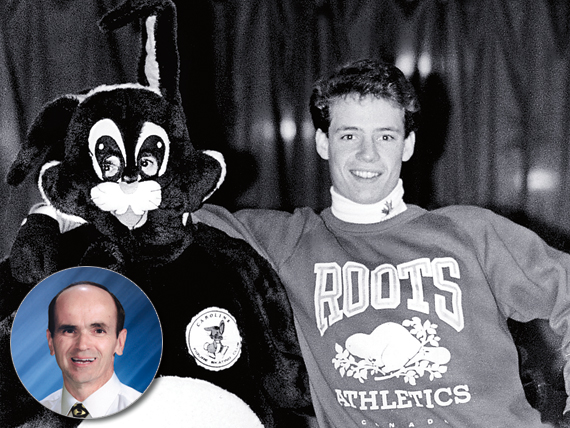

Leonard McLean, outside class, with Kurt Browning

“Now, that was much to the chagrin of my oldest daughter, who wanted the big-city life of Montréal. She’s in Edmonton right now. But my youngest daughter is in a small community too, so there’s one of each kind.”

According to Browning, nowadays it’s virtually impossible to imagine Caroline without Leonard McLean.

“He just became the kind of guy the community looks forward to seeing at events,” Browning says. “If there’s a new museum outside of town, who’s working the front gate? Lenny. He’s that kind of guy. You’re not surprised to see him.

“And when he’s not at an event, you wonder why. It’s only the really good community type of person who gets noticed in that way. And anyone who keeps getting invited to our class reunion – he has been to at least a couple – is the kind of guy kids trust.

“He became the guy who, if you had a serious problem, you’d go to Lenny.”

So, Kurt, did you ever go to Lenny with a so-called serious problem?

“I left town quite early to go and pursue this figure skating thing,” Browning says. “So right when I was getting old enough to have a problem worth talking about, I left.”

Oh well, that’s probably a win-win situation.

All things considered, Browning says, his school experience was positive.

“Yeah, I liked school. But I went to school in the days when we didn’t get pummelled with homework, and it was a really small town. So, to be blatantly honest, school wasn’t a problem.

“I can tell that school is just so much more work for kids now. It’s much more serious. Back in my day, the teachers were members of the Lions Club with your father. The gym teacher was your hockey coach, that sort of thing.”

McLean, in fact, was Browning’s hockey coach for a couple of years.

“I still go to hockey games and figure skating and curling and baseball in the summer here – it’s just me being part of the community,” McLean says. “The only times I’m not at events at home is when my grandkids are playing hockey or something and I’m probably following them around.”

Considering his own transformation from tyrant to touchstone, McLean understands it was a much different era for teachers back when he got started.

“If my teaching style hadn’t eventually been so well accepted, then maybe I would have been more inclined to move on,” he admits.

“You had to be tough – it was a tough farming community. But in those days, 99 per cent of the time a teacher would get the parents’ support. If a kid went home and said he had to be disciplined at school, he probably would be disciplined at home too.

“It was a harsher time in that way, but by the same token you could also give a kid a pat on the back and not be checking over your shoulder to see if someone was taking a picture of you. So in a lot of ways it’s harder to be an elementary school teacher today.”

When asked what advice he would give current-day teachers, McLean notably gives the same recommendation that he gave himself all those years ago.

“Chill out,” he says, simply. “You just have to relax a bit.”