Haiti after the Earthquake

by Jessica Leeder

On the sweltering June afternoon that France Saint Jeune has chosen to register his son Georgie for kindergarten, the pair finish their assigned paperwork – a few pencil-drawn house sketches for Georgie and more official documents for Saint Jeune.

They stand for a while beside their parked motorcycle at the edge of the school yard. In silence they take in the once-sprawling playground of the oldest boys’ school in Jacmel, which has been transformed into a maze of outdoor classrooms designed to hold four buildings worth of students. The classrooms house wood desks and flimsy chalkboards propped up with sticks and sections of rope. Shaded by a patchwork of plastic tarps, the rooms have no walls to buffer the voices of teachers struggling to maintain students’ attention in the late afternoon heat. Students in the last class of the day chatter as they line up, plastic buckets and bowls in hand, for the scoop of cooked rice that is supposed to keep them from going hungry.

With an hour of school left to go, small clusters of primary students begin to trickle out of class, giggling and racing each other up and down the paved walkway that leads to the school’s ruined main building. The girls’ hair ribbons flap like streamers in the breeze.

“When school reopened after the earthquake, it took away the stress the kids were going through,” says Saint Jeune, a national police officer who lives in Jacmel but makes the daily three-hour commute to his posting in Port-au-Prince. He endures the grueling schedule in part, he says, so he can afford to pay school bills for Georgie and his two older children. Since the earthquake, though, he’s begun to wonder if school is a worthy investment.

“After the earthquake they’re not getting good grades,” he says. “Haiti is a country that is very difficult. In the conditions we’re in, you can’t leave your children to be unproductive.”

The quake

It took only 35 seconds on the evening of January 12 for a massive, magnitude 7.0 earthquake to snuff out the lives of more than 200,000 people and wipe out huge tracts of the southern regions of Haiti, one of the world’s poorest countries. More than two million people were affected, according to Haiti government statistics. Three-quarters of those are currently living in camps for the internally displaced sprawled in and around the major cities that were hit: Port-au-Prince, Léogâne, Jacmel, Gonaïves, Petit-Goâve and Grand-Goâve.

The epicentre was a mere 25 kilometres west of the capital city of Port-au-Prince. Most of the government’s infrastructure crumbled, including the presidential palace, the building housing the national assembly and the central jail. The headquarters of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti also collapsed, killing the mission chief and several members of the staff.

The tranbleman tè (Creole for earthquake) also flattened a huge chunk of the education sector. Nearly 5,000 primary and secondary schools were destroyed or badly damaged according to statistics collected by Haiti’s Ministry of Education. About 38,000 students were killed, as were 1,300 teachers and education staff.

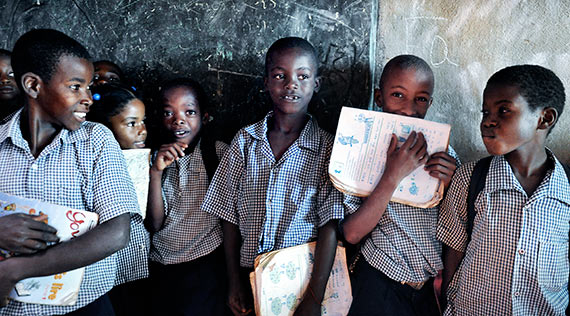

Students at école nationale de Colin in La Montagne prefer indoor classes because they are cooler and more spacious, and blackboards are fastened to the walls.

In spite of the widespread destruction, community leaders across the country agreed with Saint Jeune. Haiti’s children needed to go back to school as soon as possible.

Engineering that return in the first post-earthquake months was complicated. The massive destruction meant that camps for those with no homes had already gone up in schoolyards and on soccer pitches. Further clouding all of that was the fact that before the disaster Haiti’s education system was already a tattered patchwork in need of drastic repair.

The majority of the nation’s schools – between 80 and 90 per cent – are privately funded, some through reputable Catholic or other religious organizations and others by individual investors who see providing education as little more than a business. Haiti has no requirement that teachers be certified or even professionally trained. Many are given jobs without having completed their secondary studies.

“Most schools in Port-au-Prince are businesses,” says Kimberley Gringhuis, OCT, an Ontario teacher who has been on leave from her job with the Toronto DSB since September 2009, when she arrived in Haiti’s capital for a term as principal of Adoration Christian School. Adoration is a small but free primary school with 120 students, funded by Canadian donors. Gringhuis, who has six years teaching experience, has been working in Haiti on and off since 2005.

“The government does almost nothing for the people. You can’t blame anyone for making money on a school,” she says. “That’s what happens when a government won’t take care of its people.”

A game of jump rope gets under way during morning recess at Adoration Christian School. Kimberley Gringhuis, OCT, is its principal.

The quality of education in Haiti varies dramatically by school and even by classroom. Even government-funded schools are known for being notoriously under supplied and underfunded. Schools routinely run out of money before the academic year is finished and are unable to pay teachers their full salaries. Most schools do not provide books or teaching aids, let alone computers or a strict curriculum. Teachers spend their lessons dictating from textbooks. Students are expected to memorize class material, but little effort goes into ensuring comprehension.

“In Haiti, the books we teach aren’t based on reality. The books are old,” says Evenz Gracia, a nine-year primary school teacher at Gringhuis’s school in Port-au-Prince. He can’t help but think that the massive destruction caused by the earthquake was a testament to the weakness of Haiti’s education system.

“A lot of people who died, it was because they didn’t have knowledge,” he says, referring to the improper construction and lack of building codes that contributed to the devastation.

He and others hope that the government’s lax approach to education will change in the wake of the earthquake, the damage from which has presented the impetus to overhaul the school system.

“If anything, the government should invest in the schools. It’s a true national education that can allow everybody to be responsible for the future,” Gracia says, explaining that he thinks better and more widespread access to quality education is critical to the country’s rebuilding. “Without that, Haiti is not going to make any progress. Haiti is going to get worse,” he says.

The aftermath

On the sprawling and treeless red dirt lot that now serves as école Marie Reine Immaculée, a Catholic girls’ school on the outskirts of Jacmel, things seem the most normal at recess.

In the small sliver of time the school’s 400 students have before Sister Mary Christine rings her bell to call them back to class, uniformed girls from ages five to 13 line up to jump rope, race among the tented sun shelters that now serve as their classrooms and slurp from juice boxes, oblivious to the beating sun.

When they hear the bell the girls organize themselves into neat lines, just as they used to do at their old school, a heritage building in central Jacmel. Holding hands they trek back to their outdoor classrooms where their teachers resume the precarious task of trying to salvage the academic year while remaining attuned to their charges’ new psychological fragility.

Sister Mary Christine, director of école Marie Reine Immaculée, takes in the sight of her destroyed school.

“The children were not the same after January 12,” says Sister Mary Christine, director of the school. “They were traumatized, so we did group therapy with them, spoke with them individually about what they learned through the earthquake. We sang with them, played games with them and progressively started working on academics.”

Before they headed back to school (schools in Jacmel began reopening in mid-March, about two weeks ahead of schools in Port-au-Prince and other hard-hit areas) several hundred teachers took psychological and sensitivity training sessions sponsored by non-government aid organizations and the Ministry of Education.

When school reopened after the earthquake, it took away the stress the kids were going through.

Pastor Nicolas Derenssaint, head of the kindergarten to Grade 12 collège Adventiste in Cayes-Jacmel, has learned how to deal with the special needs of a little boy at his school who lost a twin in the crush caused by the earthquake. “I give him extra attention, play with him. We talk about other things so he can manage the trauma.”

The pastor also learned a bit about the science of earthquakes – information he and other teachers initially repeated often in the classroom to calm nervous students. Shortly after classes resumed, though, it became obvious that lessons were akin to therapy for many students whose lives had otherwise been turned upside down. Some begged to stay after class rather than return to their tent encampments.

“Some of the students have gone from living in a household with a family to living in a camp,” says Sister Mary Christine. “It amazes us to see how rapidly they regain their work ethic. There’s been big progress.”

One clear marker of that was the fact that school report cards were issued for April and May. Some students have been struggling in class, though. Most widespread, Sister Mary Christine says, are memory problems. Young students seem to have more difficulty recalling the correct spelling of certain words or the recitations they were instructed to memorize. “Some students are traumatized,” she says.

Students who arrive at class with plastic buckets or bowls are given one helping of rice – donated by the United Nations’ World Food Program.

For others, problems in class are related to hunger. In April, in hopes of jump-starting the economy and spurring displaced people to work rather than wait for handouts, the Haitian government ordered that food donations by the World Food Program (WFP) stop, with the exception of donations to schools, which still receive enough food to provide the children with one meal of rice per day. The transition was tough on families, most acutely on those who lost their homes and most of their belongings and were still struggling to find shelter.

The outdoor sites that many schools are using are not equipped with electricity or kitchen facilities. “A lot of the kids are hungry,” says Sister Mary Christine, who had to scrounge for the temporary site for her school, an empty lot on the outskirts of Jacmel that floods whenever it rains. Not having a kitchen in which to cook the WFP’s food donations to schools is a source of stress for the director. “The kids need it,” she says of the meal. “When they don’t eat in the morning, they can’t follow the class. They fall asleep.”

Siting temporary schools

Teachers and administrators, by contrast, haven’t been sleeping much at all since the schools reopened. A government edict that classes not be held in or near concrete buildings, regardless of whether or not they are damaged, is creating headaches. Many have been forced to transform their small dirt school yards into tarp-covered outdoor classrooms, which are difficult to cope with in rain or extreme heat. Those without yard space – and there are many – are competing with shelter organizations for land. Because most lots are still crowded with the rubble of crumbled buildings, the competition is stiff – and expensive.

“There is not a single piece of land around any of the schools – we’ve got to squeeze them in,” Damien Queally, Emergency Program Manager for Plan Haiti, says of the medium-term school shelters his organization is working to construct.

“Nobody has any place to do it,” he says. “This big miracle field isn’t going to show up in a city area.”

Several hundred teachers took psychological and sensitivity training sessions.

Most school directors have long realized this. Some have resorted to negotiating temporary leases with landowners to get them through the school year, even if paying for the land eats into their operation budgets. Sister Mary Christine, for example, has secured her site until August, when the extended school year is slated to end. She has no idea, she says, how she’ll cobble together enough money to lease or buy a site for rebuilding in time for September.

At isolated rural schools in mountainous regions affected by the earthquake, some school directors have simply decided to ignore the no-concrete-buildings rule and allow students back into undamaged classrooms. Pierre Louis Christnord, director of école nationale de Colin in La Montagne, an hour west of Jacmel, says he began using the old classrooms after high school students staged a protest. They tossed rocks onto the school’s corrugated-tin roof during an outdoor class that was being held underneath stifling layers of tarp.

Sister Annouse Piquion, director of the rural, semi-private école St. Joseph in Côtes-de-Fer, did not have that option. Her school of 500 students, accessible only by a tire-shredding network of rock and mud roads that are best negotiated by motorbike or mule, was damaged beyond repair. Its remote nature has prevented aid organizations from coming to the rescue with anything more than flimsy tarps.

Primary students sing in a temporary classroom set up at école frère Clement in Jacmel. The wooden structures, sponsored by the development group Plan International, are earthquake- and hurricane-proof and could last up to two decades.

Since January, she’s been spending the money she had set aside to pay her teachers’ salaries (each is supposed to receive 2,500 Haitian gourdes or $65 per month) on demolition crews and wood posts for new classrooms. She has no idea how she’ll manage to keep the school open for the remainder of the year. News that schools in other districts have already been shuttered due to a lack of funds (on June 7, 32 of 35 private schools in the Coq Chante commune of Jacmel closed because their money ran out) doesn’t help.

“We don’t know what we’re going to do because normally we’re supposed to finish the school year in June. Now it’s going to go to August,” she says. She’s constantly weighing whether it’s smarter to devote her small budget to keeping classes open or erecting new buildings.

The biggest thing they can do for Haiti is to do their homework.

“Our priority is teaching the lessons,” she says. “But it’s important for us to have a place. That’s why we want to rebuild the school.”

Administrators at Kimberley Gringhuis’s school in Port-au-Prince made a similar choice. While other schools in the city reopened in March, they held off. Their new school, a sunny lot close to the international airport on which small, wood-frame bunkers have been transformed into classrooms, opened in early June.

By then, students seemed to be less preoccupied with the earthquake and more attuned to their lessons.

“They’re more responsive. They’re asking to learn more in my classes,” says Gracia. Buoyed by their enthusiasm, he decided to up the ante on his teaching. “I talk more now about reality, the earthquake, the government, the need for people to help each other. The biggest thing they can do for Haiti is to do their homework. I want to help children have that potential within them.”