"WHEN ZAIB SHAIKH was cast as the even-tempered Amaar on CBC's Little Mosque on the Prairie, he found himself faced with a dilemma.

"How was I going to play someone who was so like me in some ways and yet so different in many others?"

He found the answer by going back to the lesson he learned from the extraordinary Lawrence Stern, his drama teacher at Streetsville SS.

"Lawrence had one motto that he drilled into us above all others: 'Role equals self plus others.' With that one tool, he enabled anyone who stepped into his classroom to play any role possible.

"So I thought about Amaar — and then Lawrence — and filtered myself through Amaar's character, and that's how it all happened."

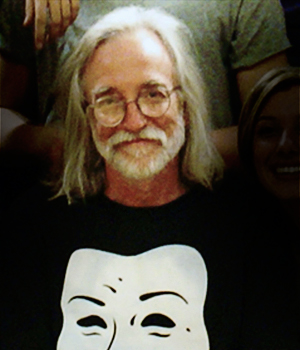

Stern passed away from cancer on August 31, 2010, shortly after retiring from a 30-year career in teaching. But his influence started long before Shaikh's television stardom and continues to this day.

"Every time I find myself thinking about my work in an original and uncompromising way, I feel that Lawrence is looking at me from out there somewhere. The magical thing about his teaching was that he didn't just help you act, he helped you think and feel and live."

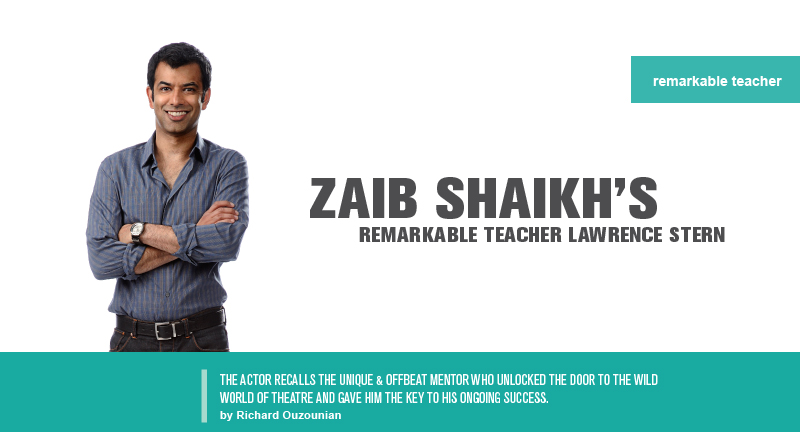

Shaikh was born in 1974 and raised in Toronto — the son of Pakistani parents who, inspired by the buzz created by Expo 67 and Pierre Elliott Trudeau, immigrated to Canada.

"There was nothing wrong with my parents' life in Pakistan. They came here because they thought it was a place where wonderful and exciting things could happen."

All of this rubbed off on Shaikh, who showed an early penchant for performing. But when Grade 9 came around, the family moved to the suburbs of Streetsville, which disoriented the young Shaikh to no small degree.

"I had been a Bloor Street West kid, and now I was going out to what I saw as the wilderness, and I didn't think there'd be any theatre there," says Shaikh.

Little did he know that Stern — in his idiosyncratic way — had been building up a drama program at Streetsville SS that was unlike any other.

"I walked in the first day to audition for the school play," recalls Shaikh, "and found out it was by Christopher Durang, who I'd never heard of." He was soon to learn that the cynically comical New York playwright was just one of the offbeat offerings with which Stern kept challenging his students.

"I auditioned and didn't get a part, which kinda weirded me out because it was the first time that had ever happened. I thought maybe I wasn't any good and that I should give this acting thing up."

Every time I find myself thinking about my work in an original and uncompromising way, I feel that Lawrence is looking at me from out there somewhere.

But the sensitive Stern picked up on Shaikh's vibe and went up to him to talk.

"I said no to you this time," Shaikh remembers his teacher saying, "but don't take that for a final answer. Keep coming to the drama club and we'll do something together for sure."

Stern had the type of look that grabbed a student's attention, with what Shaikh describes as his "deliberately mismatched running shoes, and his John Lennon hair and glasses. He was in his 40s when I met him, but he was very cool looking."

He was cool thinking as well.

In an atmosphere where acting talent was usually judged by the ability to do musicals, Lawrence bucked that trend and cultivated young performers from all disciplines. "He wasn't a proponent of standard talent. He appreciated the precocious performing kids and never put them down, but he also encouraged the silent kids who needed to be brought out of themselves."

One of the ways Stern would do this was through his method of classroom instruction, which went back to the roots of Socratic dialogue.

"He made the assumption that theatre was important to you, so he talked to you to share and debate — not to teach. You'd find yourself in a sophisticated conversation with him. He wasn't a pedant. He was an encourager of conversation, and he'd just start talking to you and you had to keep up."

Because of Stern's choice of plays, that wasn't always easy.

"I played the lead in Morris Panych's 7 Stories when I was just a teenager," Shaikh says, "and did Algernon in The Importance of Being Earnest , staged in the round. Sometimes we'd perform scenes from Ibsen's Ghosts , and we mounted a hippie maypole production of A Midsummer Night's Dream where I played Lysander."

And with Stern, field trips weren't ordinary outings to Stratford or the Shaw Festival. "He would fly under the radar and take us to see crazy things like White Biting Dog , George F. Walker plays or wild pieces of environmental theatre.

"It's important to remember that Lawrence was also friends with all kinds of people in the theatre community — from playwright James Reaney to actor-director David Ferry — and he would extend those friendships to us as well."

Shaikh laughs as he recalls one of the most out-of-the-box things that Stern did with his class. "Every year there was an arts day at school, and I guess we were all expected to put on some kind of little play or sketch, but that's not what Lawrence had in mind.

"Instead, he took us all out of the building for the day to discuss what art meant to us on a personal level. The principal went ballistic because that's not what he thought should be happening."

In the end, one of Stern's most lasting achievements was his ability to make each student feel unique, and Shaikh recalls Stern's personal gift to him in this regard.

"My real first name is Aurangzaib, but since people had such trouble saying or remembering it, I always shortened it to Zaib." Of course that wouldn't do for Stern. When he first met Shaikh, he said, "You're Aurangzaib Shaikh, named after the last great Mughal Emperor. John Dryden wrote a play about you."The magical thing about Lawrence Stern's teaching was that he didn't just help you act, he helped you think and feel and live.

"He knew something about me that no one else did," recalls Shaikh.

In the final days of Stern's life, his past students reached out to him in various ways. Shaikh did it through the media.

"I was guest hosting [the CBC radio show] Q that week — which I knew would have made Lawrence proud — so I gave him a shout-out on the radio. Two days later, he died. He was in palliative care in Oakville, in a beautiful place surrounded by gardens. Gardening was one of his secret passions."

Stern's love of gardening comes as no surprise, knowing that he spent his life cultivating talent and encouraging personal growth.