by Laura Bickle

Why do some students succeed while others fail? This is one of the questions that’s been plaguing bestselling author and New York Times Magazine journalist Paul Tough. He’s turned to neuroscientists, educators and experts in economics for an answer and shared his surprising and often counterintuitive discoveries in his latest book, How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character. Tough, who grew up in Toronto, shares how his findings can play out in the classroom.

What part does character play in student success?

What part does character play in student success?

We often think of character as being the morals and values we possess, but the educators I’m writing about look at it as a set of skills — like grit, zest and optimism. These traits don’t make you a good or a bad person, but they can help you achieve what you want out of life.

How can teachers help develop these strengths?

How can teachers help develop these strengths?

There’s a teacher in Brooklyn who has created the best middle-school chess team in the US by having her students take an honest look at their losses. The research is clear; learning how to deal with failure is an incredibly valuable skill for a student to possess, and the earlier they can learn how to harness it, the better. Being able to “practise” failing in Grade 6 is a gift. It better prepares you for the bigger hurdles you’ll encounter later in life.

What were you most surprised to discover during your research?

What were you most surprised to discover during your research?

When I started out, I truly believed that standardized test scores were a really good predictor of who’d succeed over time, but there are countless examples where that isn’t the case. If you possess grit, and self-control and perseverance — it makes a huge difference. You can overcome poor standardized test scores with these character strengths.

How has your opinion regarding standardized tests changed?

How has your opinion regarding standardized tests changed?

It’s made me more skeptical. What I now know is that the skills that allow students to do well on these tests are not the skills that will really matter to them in the long run. I don’t think we should do away with standardized tests, but I do think we need to lower the stakes so that they become more of a diagnostic tool, rather than the focus of any given teacher or school.

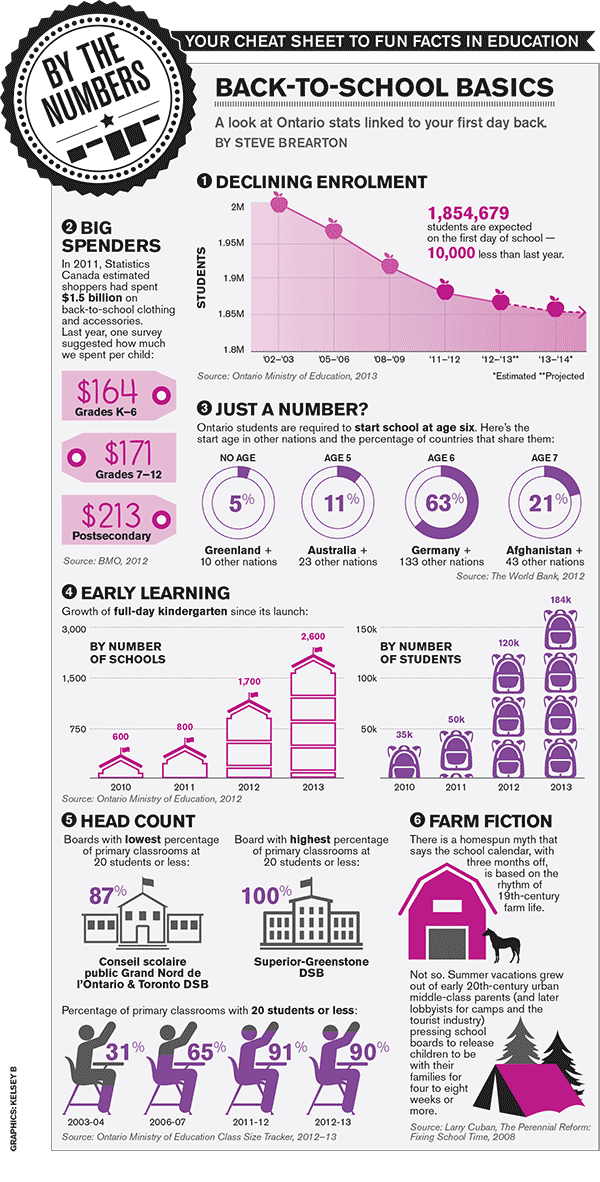

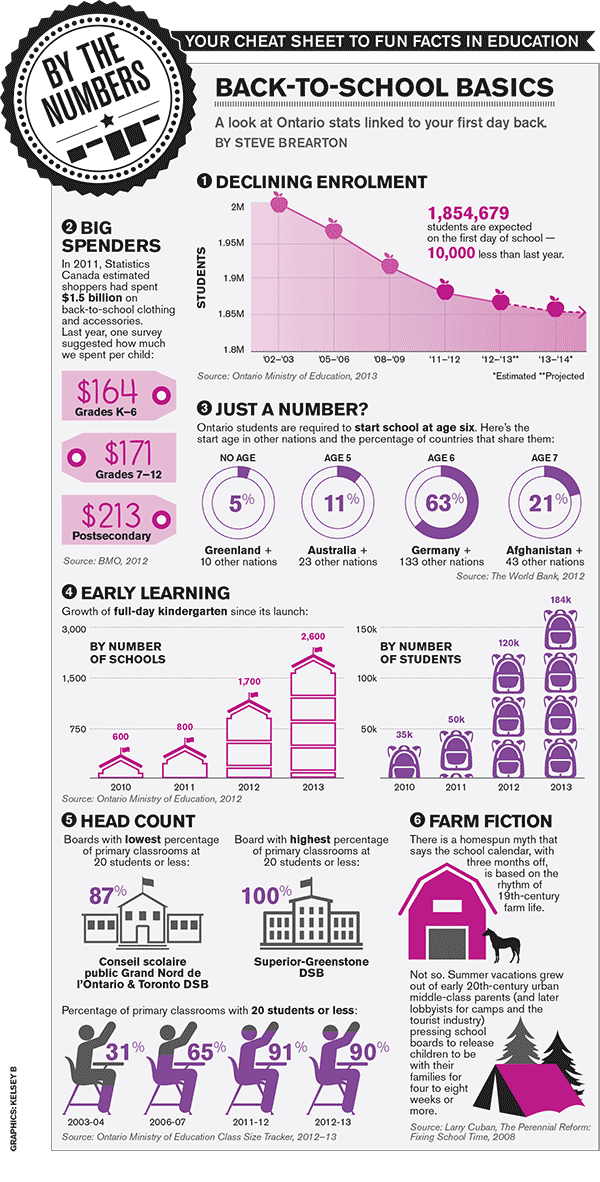

By The Numbers

BACK-TO-SCHOOL BASICS

A look at Ontario stats linked to your first day back.

By Steve Brearton

Declining enrolment

- 1,854,679 students are expected on the first day of school

- 10,000 less than last year.

Source: Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013

Big spenders

In 2011, Statistics Canada estimated shoppers had spent $1.5 billion on back-to-school clothing and accessories. Last year, one survey suggested how much we spent per child:

- Grades K–6: $164

- Grades 7–12: $171

- Postsecondary: $213

- Source: BMO, 2012

just a number?

Ontario students are required to start school at age six. Here’s the start age in other nations and the percentage of countries that share them:

- NO AGE: 5% (Greenland + 10 other nations)

- Age 5: 11% (Australia + 23 other nations)

- Age 6: 63% (Germany + 133 other nations)

- Age 7: 21% (Afghanistan + 43 other nations)

Source: The World Bank, 2012

Early learning

Growth of full-day kindergarten since its launch:

BY NUMBER OF SCHOOLS

- 2010: 600

- 2011: 800

- 2012: 1,700

- 2013: 2,600

BY NUMBER OF students

- 2010: 35k

- 2011: 50k

- 2012: 120k

- 2013: 184k

Source: Ontario Ministry of Education, 2012

head count

Boards with lowest percentage of primary classrooms at 20 students or less:

Conseil scolaire public Grand Nord de l’Ontario & Toronto DSB: 87%

Board with highest percentage of primary classrooms at 20 students or less:

Superior-Greenstone DSB: 100%

Percentage of primary classrooms with 20 students or less:

- 2003-04: 31%

- 2006-07: 65%

- 2011-12: 91%

- 2012-13: 90%

Source: Ontario Ministry of Education Class Size Tracker, 2012–13

farm fiction

There is a homespun myth that says the school calendar, with three months off, is based on the rhythm of 19th-century farm life.

Not so. Summer vacations grew out of early 20th-century urban middle-class parents (and later lobbyists for camps and the tourist industry) pressing school boards to release children to be with their families for four to eight weeks or more.

Source: Larry Cuban, The Perennial Reform: Fixing School Time, 2008

What part does character play in student success?

What part does character play in student success?